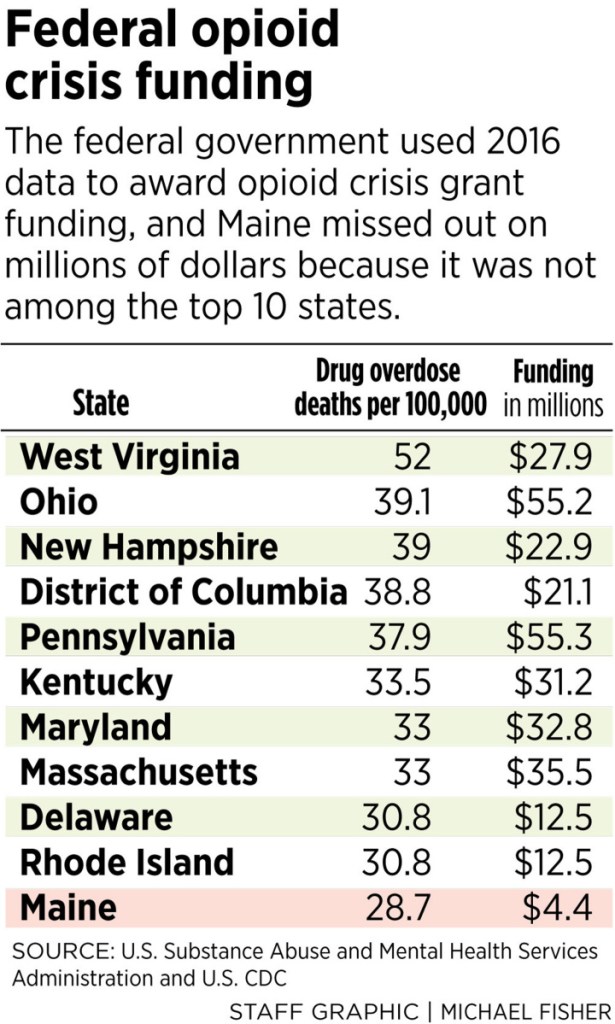

After drug overdose deaths rose to record levels in Maine in 2017, the Trump administration used 2016 data in the funding formula for a grant program, depriving the state of millions of additional dollars to support treatment and prevention programs for the opioid epidemic.

The formula – created by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration – gave extra funds in September of this year to the 10 states with the highest drug overdose death rates per capita. Rather than use overdose data from 2017, when Maine was ranked ninth in the nation, the agency used data from 2016, when Maine was ranked 11th.

As a result, the state missed out on at least $8 million in additional funding at a time when more than one Mainer per day, on average, is dying of an overdose. Maine had 418 overdose deaths in 2017, and 180 through the first six months of 2018. In 2016, Maine had 376 drug overdose deaths.

“The need was only microscopically different between the 11th- and 10th-place states, and yet the funding we received was millions less. It makes no sense,” said Malory Shaughnessy, executive director of the Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services, Maine, a trade association of behavioral health nonprofits.

Shaughnessy said funding is greatly needed for treatment and support services, such as housing and peer support.

For the next round of funding, members of the state’s congressional delegation are urging the Trump administration to modify the opioid grant award formula to eliminate the “cliff” effect, which sharply reduces funding for states that are just outside a select statistical group.

SUDDEN CUTOFF ‘ILLOGICAL’

Maine received $4.4 million in September for its 11th-place position in 2016 opioid overdose death rates. Delaware and Rhode Island tied for 10th place in the death rate, and each received $12.5 million – nearly triple what Maine did, even though both states have smaller populations than Maine.

New Hampshire, which has a similar demographic makeup and population to Maine, received $22.8 million. It had the third-highest per capita overdose rate in the nation in 2016.

Dr. Lisa Letourneau, associate medical director of Maine Quality Counts and an opioid treatment expert, said states that have experienced a worse opioid problem should receive more funding, but there shouldn’t be a sharp drop-off.

“It seems rather illogical,” Letourneau said. “There should not be this sudden cutoff.”

If the funding formula had used overdose data from 2017 rather than 2016, Maine would likely have received millions more in funding. But the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which compiles national overdose data, did not publish state-by-state comparisons before the opioid funds were granted.

The money awarded in September came through the State Opioid Response grant program, using funding from the 21st Century Cures Act. The act was signed into law in December 2016, in the waning days of the Obama administration.

It’s not clear yet what funding formula will be used when SAMHSA doles out money next year, but Congress set aside $1.5 billion in State Opioid Response grants to hand out to states, probably next fall. In the second round, states that have more acute opioid problems will receive higher grant amounts.

“We simply do not know how much each state will receive (in 2019) or the precise calculation,” said Rob Morrison, executive director of the Washington-based National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors. Morrison said coming up with a fair formula is a “tough job.”

MAINE DELEGATION WEIGHS IN

Maine’s congressional delegation is already pressing for an improved funding formula for 2019.

U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree, D-1st District, highlighted the formula for the 2018 grant awards in a statement.

“The sharp difference in funding for states that fall outside of the administration’s formula is deeply concerning and has put Maine at a disadvantage when resources for treatment and prevention are so critically needed. I’m pushing SAMHSA to make sure that Maine is more fairly represented in the next round of funding,” Pingree said.

U.S. Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, a member of the Senate Appropriations Committee, said in a statement that the panel is working on fixing the funding “cliff” issue.

“The Senate Appropriations Committee is deeply concerned about the creation of funding ‘cliffs’ affecting states with high rates of opioid addictions and deaths,” Collins said. “I am working with other members to ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services prevents any future ‘cliffs’ from occurring during the second round of funding.”

In June, the Appropriations Committee recommended to SAMHSA that for 2019, the formula should “avoid a significant cliff between states with similar mortality rates.”

Collins’ office said that overall, Maine received $16.9 million in federal funding from a variety of sources for the opioid crisis, including money designated for community health centers, rural communities, treatment, Native Americans and for children who were victims of crimes related to opioid use.

Emily Spencer, Maine Department of Health and Human Services spokeswoman, said the state plans to spend the $4.4 million State Opioid Response grant it received on treatment in emergency rooms, jails, and on peer recovery programs, employment specialists and prevention.

However, with less than three weeks left in the LePage administration, most of the spending decisions will likely be made by the administration of Gov.-elect Janet Mills, who will take office on Jan. 2.

Send questions/comments to the editors.