Happy with its form of town government, the citizens of Auburn appeared unimpressed in 1868 when the Maine Legislature approved Auburn’s bid to incorporate as a city. The little town on the west side of the Androscoggin River rejected the proposal in a townwide vote.

The incorporation from a town to a city was not valid until the citizens approved the change.

During the next year, attitudes slowly began to soften. On the day of a second vote on Feb. 22, 1869, the Lewiston Evening Journal wrote: “The feeling has been gaining ground that a city charter would confer many benefits and privileges not heretofore enjoyed.”

On Feb. 22, 1869, fewer than two-thirds of Auburn voters adopted the measure, 452-365, to become Maine’s 13th city. Thomas Littlefield was Auburn’s first mayor.

On its 150th anniversary since becoming a city, Auburn is throwing a citywide birthday bash. Free cake will be available at 29 locations Friday throughout Auburn and one location in neighboring Lewiston.

Friday’s festivities will kick off Auburn’s yearlong celebration of its sesquicentennial. Other events planned throughout the year include a Memorial Day parade, a summer festival, an Edward Little homecoming celebration, a Riverwalk Blues and Arts festival and a holiday parade.

Here’s a snapshot look at Auburn through the years.

Early history

While still part of Massachusetts, Auburn was carved out of the Pejepscot Purchase and named Bakerstown Plantation, which included part of Auburn, Mechanic Falls, Minot and Poland. The 1790 Census listed 217 households with 656 males and 619 females.

The first settler in Auburn’s downtown district is believed to have been Joseph Welch, who worked as a log driver and built a log cabin near West Pitch in 1797.

The town was known as both Poland and Minot before being incorporated as the town of Auburn on Feb. 24, 1854.

The name is believed to have come from a 1770 poem “The Deserted Village” written by Oliver Goldsmith. Popular in the 18th and 19th centuries, the opening line of the poem is “Sweet Auburn! loveliest village of the plain.” Legend has it that the wife of James Goff Jr., an early merchant, selected the name.

Auburn annexed land from several surrounding communities, including all of Danville in 1867 and parts of Poland and Minot, to become one of the largest municipalities in the state with 65.74 square miles.

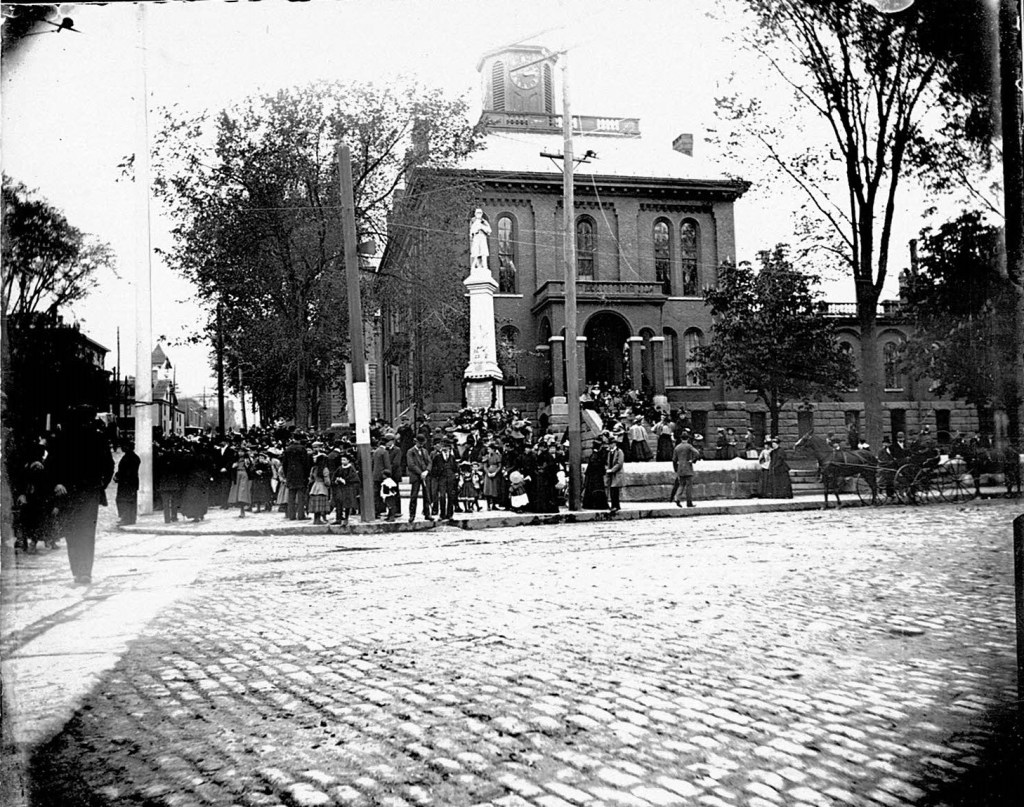

County seat

Auburn was part of Cumberland County and Lewiston was in Lincoln County in the mid-1800s when local residents, tired of the long commute to conduct county business, sought to form a new county.

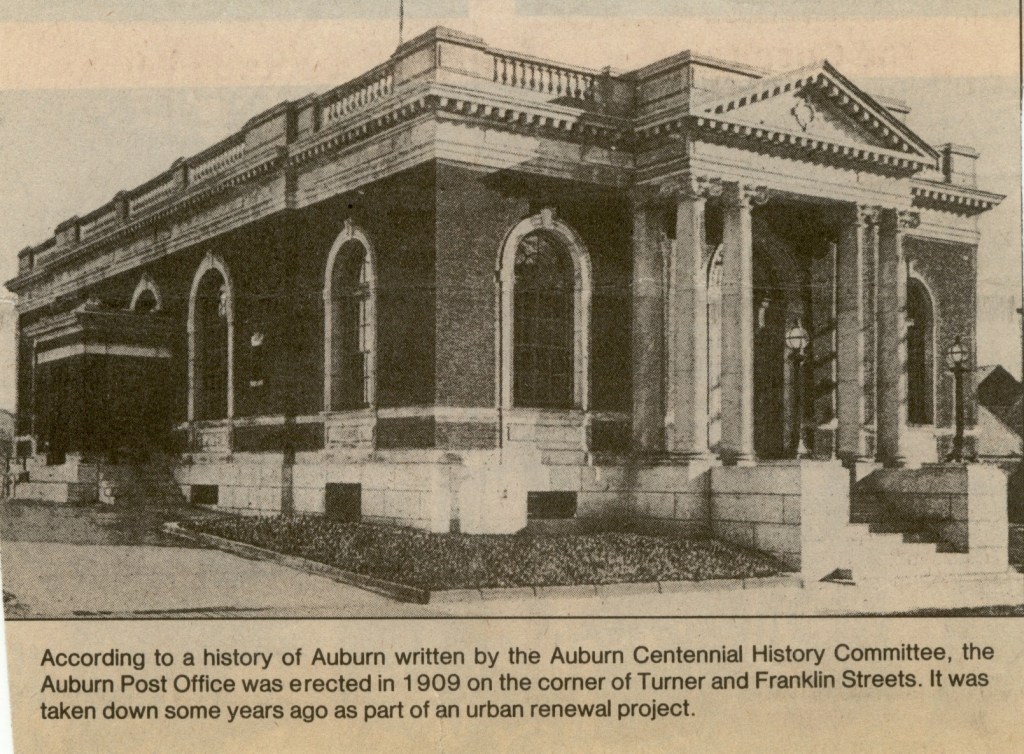

County Building

It made sense for the two towns on opposite sides of the river to belong to the same county. Androscoggin County was formed in 1854, adding towns from Cumberland, Lincoln, Oxford and Kennebec counties.

The question of where to establish the county seat came down to a battle between Auburn and Lewiston. An act in the Legislature that created Androscoggin County with Lewiston serving as a temporary county seat until an election could be held was passed March 18, 1854. The referendum would list Lewiston, Auburn and Danville as potential choices. It is believed that Lewiston officials had Danville included to split the Auburn vote.

The resulting campaign brought charges of corruption as Lewiston and Auburn used incentives and other means to persuade the county voters.

Lewiston promised to bear much of the cost of construction of the county building and the initial cost of operations, except the jail. Lewiston sent a letter to voters in the outlying towns which said, “Any town voting to make Lewiston the county seat would be relieved of any financial burden in the matter,” according to the book “Frontier to Industrial City: Lewiston Town Politics.”

According to the book, Auburn officials found out about the letter on the day before the election and sent a representative to each town to speak at their town meetings. Each rep brought a bundle of cash “equivalent to the town’s estimated share” to convince the towns that building the county seat in Auburn would cost them nothing.

With no interest in becoming the county seat, Danville overwhelmingly supported Auburn. In the end, despite Lewiston having more voters, Auburn won the race by a vote of 2,909 to 2,041. Looking at each town’s vote, Auburn’s selection is largely attributed to the fact that more voters lived on the west side of the river than the east side. The towns favoring Auburn were on the west side of the Androscoggin.

The number of voters in the election for the county seat surpassed the number of ballots cast for Maine’s governor one month earlier.

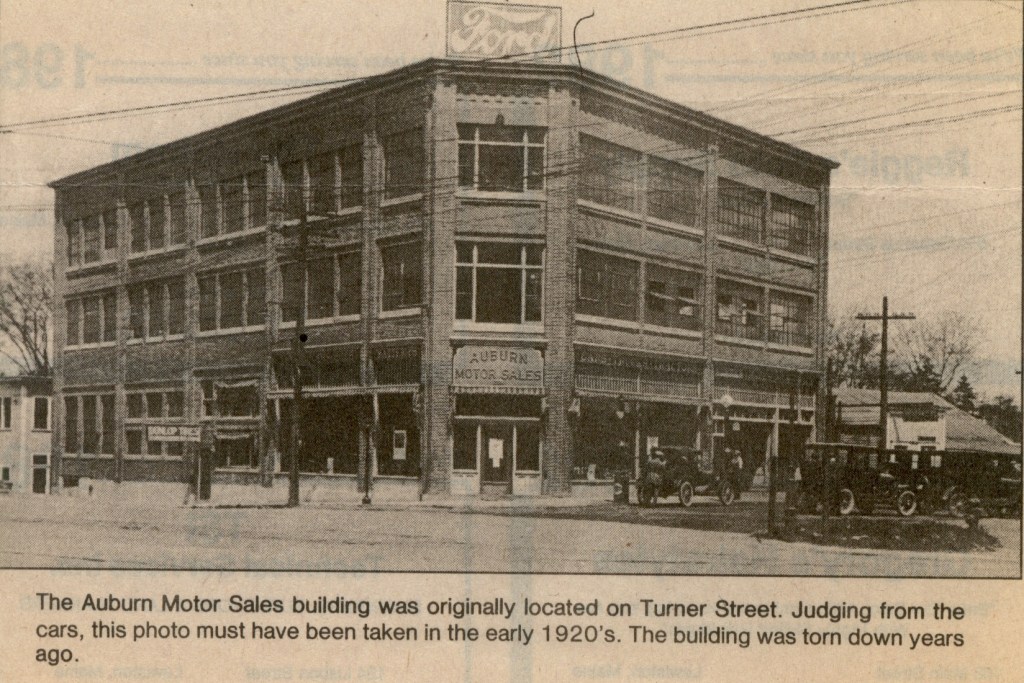

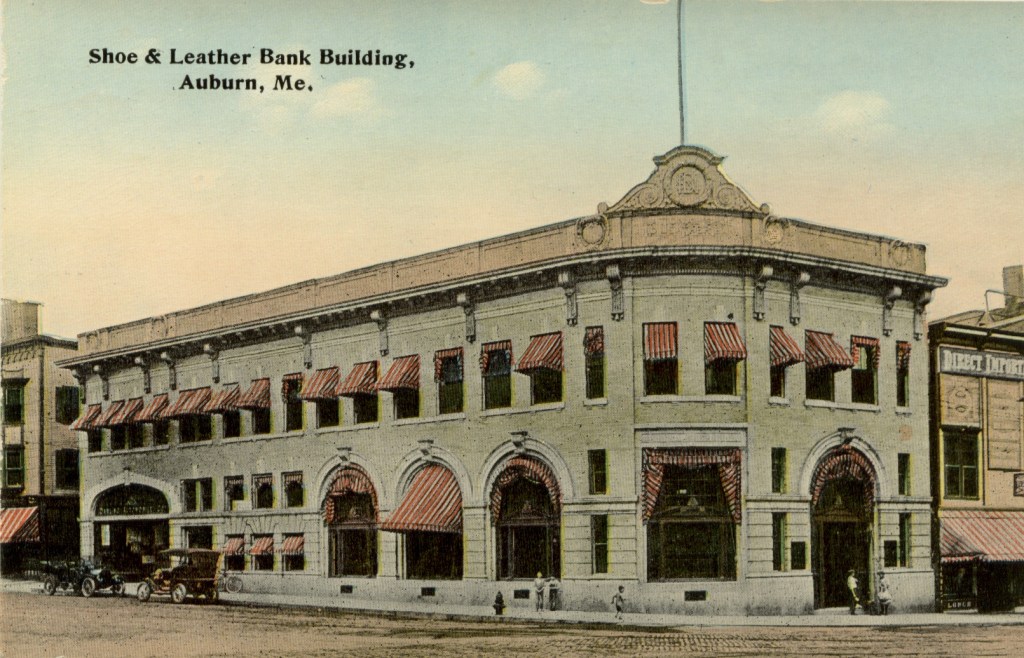

Shoe capital of Maine

The importance of the shoe industry to Auburn’s growth is evidenced by the city seal, which features a spindle with a shoe on the end of each spoke.

Cushman-Hollis Shoe Factory and the Free Baptist Church

The industry began modestly in the 1830s when a number of cobblers opened up shop. The first shoe factory opened in 1835 by Joseph Roak in a part of Minot that eventually became West Auburn.

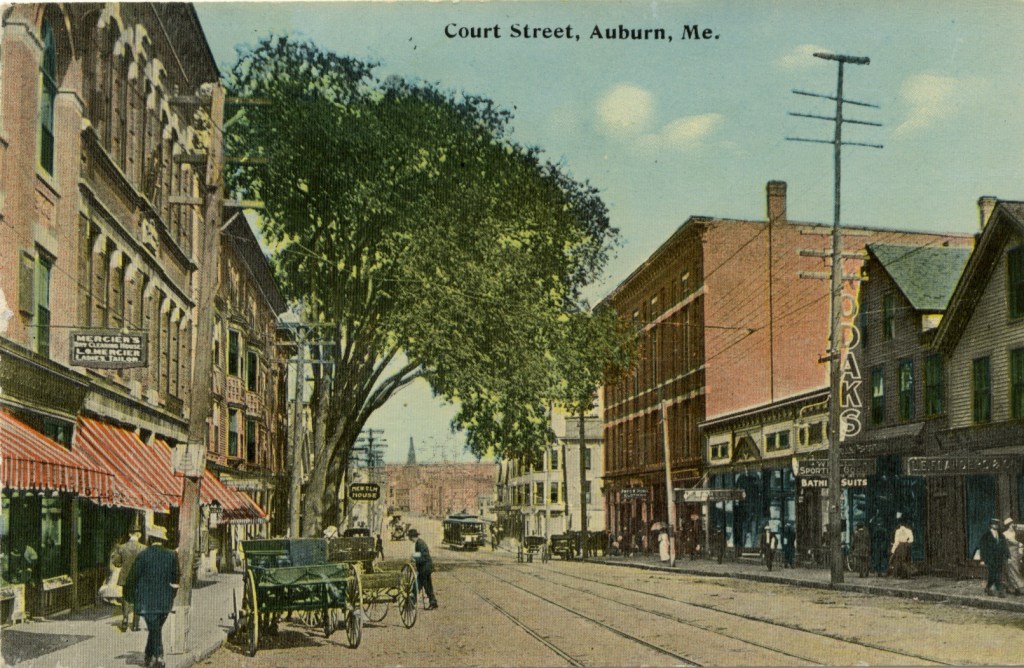

Roak eventually moved his operation to the Goff Corner section of Auburn at Main and Court streets to take advantage of the new railroad that connected the area to Portland. Several other shoe manufacturers that started in West Auburn migrated to Goff Corner.

The steady growth of the industry fueled Auburn’s economic growth. By 1859, there were 25 shoe or boot manufacturers clustered near Goff Corner.

The industry’s growth accelerated even more during the Civil War, making Auburn the shoe capital of Maine.

The shoe industry prompted a growth spurt as Auburn’s population doubled to more than 6,000 by 1870 and grew to 9,555 by 1880.

Auburn’s downtown continued to boom as the large brick buildings along Main Street, such as the Phoenix Block (1856), Pickard Block (1871) and the Roak Block (1871) — all still standing — housed shoe factories.

Asa Cushman, an early Auburn shoe baron, owned what was reported to be the largest shoe factory in the country under one roof in the late 19th century.

One Auburn manufacturer reportedly made 75 percent of all white canvas shoes in the U.S. in 1917.

Lake Grove Park

Seeking a way to increase ridership, the Lewiston and Auburn Horse Railway developed an entertainment and recreational site on the shores of Lake Auburn. Lake Grove opened in 1883 along the eastern shore.

A popular place for picnics, attractions at Lake Grove included a bowling alley, roller skating rink, a large number of boats and an open-air theater.

The steamship Lewiston could give up to 20 people a 30-minute ride around Lake Auburn and would stop at the Lake Auburn Mineral Spring House, which was open from 1889-1993 until it burned down. The foundation of the Spring House remains near Spring Road.

North Auburn

Adjacent to Lake Grove was the Lake Grove House, a three-story hotel with a three-sided veranda that catered to out-of-state guests and fishing parties.

By the 1920s, officials were looking long term to limit recreation and other activities along Lake Auburn to protect the drinking-water supply. The growing number of cars were also starting to deplete the number of passengers riding the trolley, which had opened the park.

The park eventually closed in 1928.

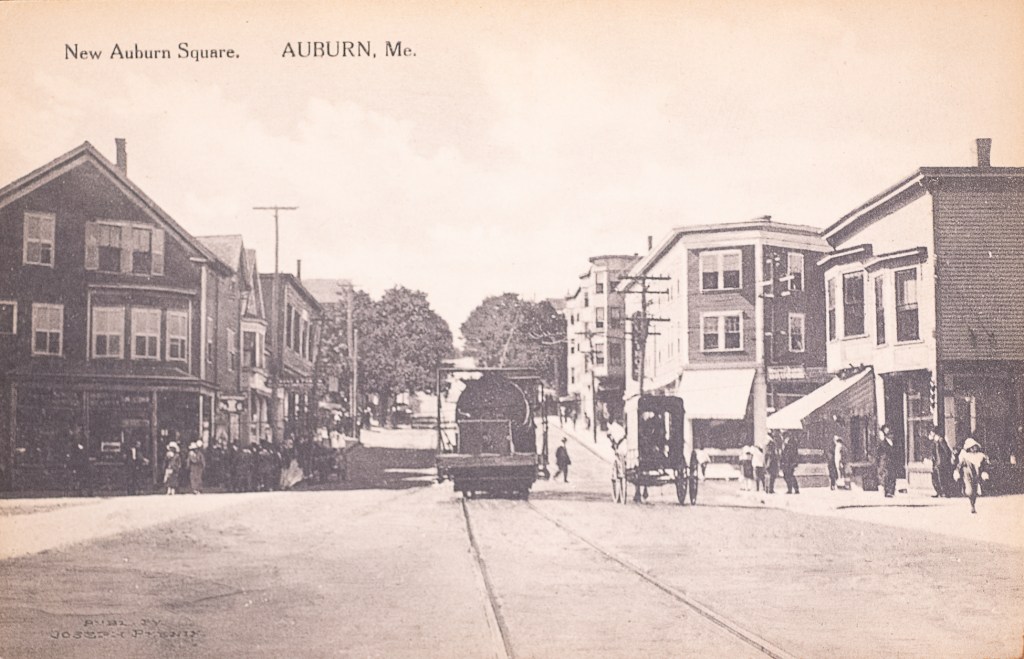

New Auburn fire

Much of New Auburn changed forever when a 1933 fire destroyed several blocks of the village.

1933 fire in New Auburn Andree Kehn

The fire began on Mill Street, where the Pontbriand Building is located. An 11-year-old boy started the fire behind a car repair shop and a gas station. The dry conditions and strong winds helped the fire spread quickly, engulfing city blocks densely filled with three- and four-story wooden tenements, which housed many immigrant families.

Lack of water pressure plagued firefighters. The pressure was too weak for the water to reach the upper floors of the apartment buildings, according to coverage in the Lewiston Daily Sun.

The direction of the wind prevented the burning embers from jumping the river and lighting the densely packed apartments in the Little Canada section of Lewiston across from St. Mary’s Church, which is now The Dolard & Priscilla Gendron Franco Center.

It took firefighters from 12 towns more than six hours to get the massive fire under control.

An estimated 249 buildings were destroyed between Pulsifer and Loring streets. A total of 422 families and 2,167 individuals were left homeless, according to a report by the National Fire Protection Association.

The area of New Auburn that was flattened included large swaths of First, Second and Third streets and a section of Fourth Street.

Miraculously, no one was killed.

According to published reports, damage was estimated at more than $2 million. In addition to the loss of several dozen tenements, buildings destroyed included a synagogue and two schools — Wilson School and St. Louis School.

The venerable St. Louis Catholic Church, built of brick and located at the southern edge of the destruction, survived the fire.

The fire led to changes in fire and building codes.

Shoe strike

An ugly chapter in the history of the Twin Cities was the Shoe Strike of 1937. Thousands of workers walked off the job in March to protest low wages and call for better conditions and union representation.

Charles Ault Andree Kehn

Organizers from the Congress of Industrial Organizations, led by Powers Hapgood, saw opportunity in the Twin Cities because of Maine’s low wages and lack of a labor union.

Mill owners saw no need to speak with the CIO officials. The workers voted to strike.

Things did not go as planned. Replacement workers were hired and police guarded the mills.

One month later, the protests turned violent, when workers clashed with police on Court Street. Maine Gov. Lewis Barrows called in eight National Guard units to help quell the riot. Authorities used clubs and tear gas to regain control.

The court issued an injunction against the strikers and several organizers were jailed.

The strike ended in late June. Some of the strikers never regained their jobs because of the replacement workers.

All-America city

Seeing a couple of other Maine cities earning the distinction, Auburn applied in 1967 to become an All-America city. The program, which began in 1949, was sponsored by the National Municipal League and Look Magazine.

The award recognizes how communities overcome challenges and weakness through civic engagement.

The city, led by Mayor Harry Woodard Jr., used the decline of the shoe industry and the growth of different industrial manufacturers as the centerpiece of its application.

Jimmy’s Diner

“In the early 1960s, Auburn’s economy, which was largely dependent on shoes and textiles, was faced with rising unemployment and mass exodus of its young people and general economic and community deterioration. Her citizens responded to this plight by undertaking an ambitious program of industrial development,” according to the application.

The Auburn Business Development Corp. helped broker deals to bring General Electric and Tambrands to the city in 1967. Along with the earlier arrivals of Pioneer Plastics and Goodyear Rubber, later known as Anthoine Rubber, this brought 1,300 new manufacturing jobs to the city.

The city also stressed an urban renewal and beautification program with rejuvenation of the community.

Auburn was one of 11 municipalities chosen across the country, including Fresno, California, South Bend, Indiana, and Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

Send questions/comments to the editors.