In 2011, days after Donald Trump challenged President Obama to “show his records” to prove that he hadn’t been a “terrible student,” the headmaster at New York Military Academy got an order from his boss: Find Trump’s academic records and help bury them.

The superintendent of the private school “came to me in a panic because he had been accosted by prominent, wealthy alumni of the school who were Mr. Trump’s friends” and who wanted to keep his records secret, recalled Evan Jones, the headmaster at the time. “He said, ‘You need to go grab that record and deliver it to me because I need to deliver it to them.’ ”

The superintendent, Jeffrey Coverdale, confirmed Monday that members of the school’s board of trustees initially wanted him to hand over Trump’s records to them, but Coverdale said he refused.

“I was given directives, part of which I could follow but part of which I could not, and that was handing them over to the trustees,” he said. “I moved them elsewhere on campus where they could not be released. It’s the only time I ever moved an alumnus’ records.”

The former NYMA officials’ recollections add new details to one of the allegations that Michael Cohen, the president’s longtime personal lawyer and fixer, made before Congress last week. Cohen, who told the House Oversight and Reform Committee that part of his job was to attack Trump’s critics and defend his reputation, said that Trump ordered him “to threaten his high school, his colleges and the College Board to never release his grades or SAT scores.”

Trump has frequently boasted that he was a stellar student, but he declined throughout the 2016 campaign to release any of his academic records, telling The Washington Post then, “I’m not letting you look at anything.”

Last year, he said he “heard I was first in my class” at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton business program, where he finished his undergraduate degree, but Trump’s name does not appear on the school’s dean’s list or on the list of students who received academic honors in his class of 1968.

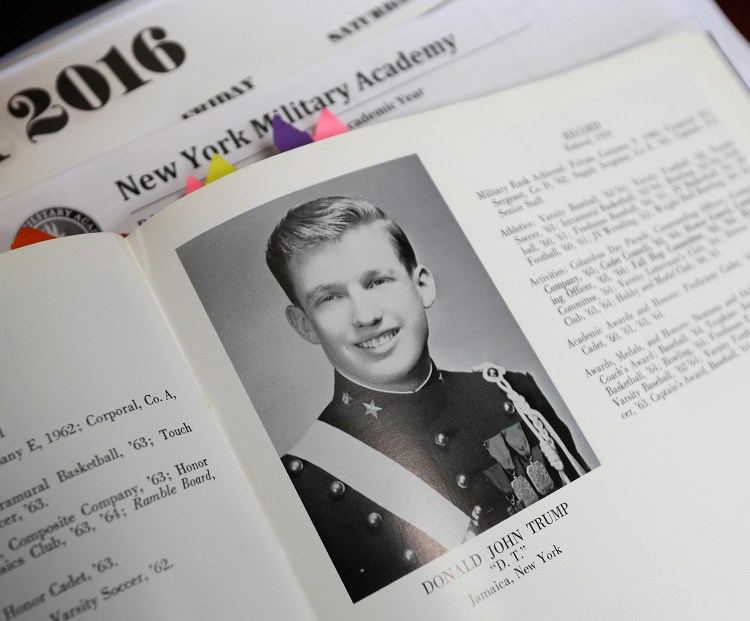

Trump spent five years at the military academy, starting in the fall of 1959, after his father – having concluded that his son, then in the seventh grade, needed a more discipline-focused setting – removed him from his Queens private school and sent him Upstate to NYMA.

At the academy, which modeled its strict code of conduct after the nearby U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Trump loved competing to win contests for cleanest room or best-made bed. Although not known as an academic standout, he was a prominent baseball player and was well known on campus for bringing women there and showing them around. Despite getting a series of Vietnam War medical deferments for bone spurs in his feet, Trump has said that his military academy background provided “more training militarily than a lot of the guys that go into the military.”

Trump told The Post during the 2016 campaign that he “did very well under the military system. I became one of the top guys at the whole school.”

He said his parents originally sent him there because “I was a wise guy, and they wanted to get me in line.”

Jones and Coverdale declined to disclose the contents of his transcript.

Those who were aware of the 2011 effort to conceal Trump’s records said the request set off a frenzy at the military academy.

“I know for a fact that in 2011, the decision was made by the superintendent to remove those records and secure them so no one on the staff could get to them,” said Richard Pezzullo, a graduate who worked closely with school officials in a drive to save the school, which was then in financial distress. “People had been making inquiries, and there was a paramount interest in securing those records.”

The boarding school had no formal archive at the time. Jones said he combed through the basement of Scarborough Hall on the academy’s sprawling campus, 60 miles north of New York City, and found the real estate mogul’s transcript in file cabinets containing student records.

“I don’t know if we should be doing this,” Jones recalled telling his boss. “He told me that several wealthy alumni, including a close friend of Mr. Trump, were putting a lot of pressure on the administration to put the record in their custody for safekeeping.”

Jones said he did not know whether the original request to remove Trump’s records from the files came from Cohen.

Coverdale declined to say where he hid Trump’s records or to identify the people who ordered him to pull them out of the school’s files. “I don’t want to get into anything with these guys,” he said. “You have to understand, these were millionaires and multimillionaires on the board, and the school was going through some troubles. But to hear, ‘You will deliver them to us?’ That doesn’t happen. This was highly unusual.”

The White House did not provide a response to The Post’s request for comment Monday. Leaders of the academy’s board from that time also did not respond to requests for comment. Nor did Cohen or the school’s current superintendent, Jie Zhang.

The academy closed in 2015 after filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, but it quickly reopened after a nonprofit entity led by a Chinese investor, Vincent Mo, bought it at a bankruptcy auction and said it would pay off the school’s $16 million debt.

Cohen said last week that he had sent threatening letters to Trump’s schools, warning that “we will hold your institution liable” if any of his records were released. In his letter to the president of Fordham University, where Trump spent his first two years of college, studying business administration, Cohen demanded that the records be “permanently sealed” and said any release was “criminality,” which “will lead to jail time.”

A Fordham spokesman last week confirmed that the school received Cohen’s letter, as well as a call from the Trump campaign, and responded that the university was bound by federal law not to reveal any student records without Trump’s permission. A spokesman for the University of Pennsylvania declined to comment.

In 2011, when the military academy was asked to secure Trump’s records, he had not entered politics formally. But he was considering challenging Obama in the 2012 election and had been making the rounds on TV, stepping up his criticism of the president, including insinuating that Obama was not qualified for admission to Columbia, where he finished his undergraduate degree, or Harvard, where he went to law school and graduated magna cum laude. During the 2012 campaign, Trump offered to donate $5 million to charity if Obama released his college transcripts.

At New York Military Academy, the decision to remove Trump’s records from the files was unique, said Jones, a management consultant who served as headmaster from 2010 to 2011. “It was the only time in my education career that I ever heard of someone’s record being removed,” he said. “But people were fearful as a result of whatever call was made from Mr. Trump’s friends. I was told we’re getting a lot of heat about this.”

Coverdale, who was the school’s superintendent from 2010 to 2013 and is now a public school administrator in Florida, said he does not know what happened to Trump’s file after he left the academy in 2013.

The school’s willingness to move the records stemmed from Trump’s special status and the school’s precarious position at the time, according to several academy graduates and former staff members.

The academy, founded in 1889, has had a mixed relationship with Trump through the years.

The school was in debt, and was openly discussing selling its 113-acre campus and shutting down, when a group of graduates and others trying to save the school visited Trump at his Manhattan office in 2010. The group was seeking a $7 million donation that they hoped to use to raise an additional $30 million from graduates and other sources.

The meeting did not go well.

First, Pezzullo, Trump’s fellow graduate, spilled a glass of Diet Coke on Trump’s cream-colored carpet, which caused Trump to blurt an expletive, according to two participants in the meeting.

Then, according to Pezzullo, when the school’s graduates made their pitch, Trump responded by asking, “What do I get for my $7 million?”

The military academy was prepared to offer to name a summer program, a building or potentially even the school itself after Trump, according to academy officials.

But Trump said no investment in the school was worthwhile. “It’s not a good business proposition,” he said, according to Pezzullo. “The school has had a good run.”

A decade before that meeting, Trump offered to build a facility on campus in honor of his coach and mentor, Theodore Dobias, according to two former school officials. But the school’s board turned down the offer, preferring a cash donation. Trump, who had “just wanted to build something for this man he loved,” gave nothing, Pezzullo said.

The Trump Tower meeting in 2010 ended with Trump’s “firm ‘No,’ very polite, but firm,” Pezzullo said.

After the meeting with Trump, the group from the academy met with Cohen, who delivered the same message but in a less gracious manner.

“Cohen told us he would love to have enough money to buy the school so he could bulldoze it,” Pezzullo said.

Michael E. Miller and Karen Heller contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.