ELIOT — It takes a trained eye to spot the metal sheaths enveloping electrical lines strung along Route 101 here. But to Lloyd Hendrix, they are easy to see, and each one tells a story.

Hendrix, manager of process and technology for Central Maine Power, was driving the rolling hills of forest and farmland recently to show why this stretch of rural highway near the New Hampshire border has one of the worst records of power outages in the company’s service territory. Those metal sheaths mark where wires were broken and have been spliced over time, typically victims of trees weakened by decay, branches buffeted by storms or weak poles that snapped and pulled down lines.

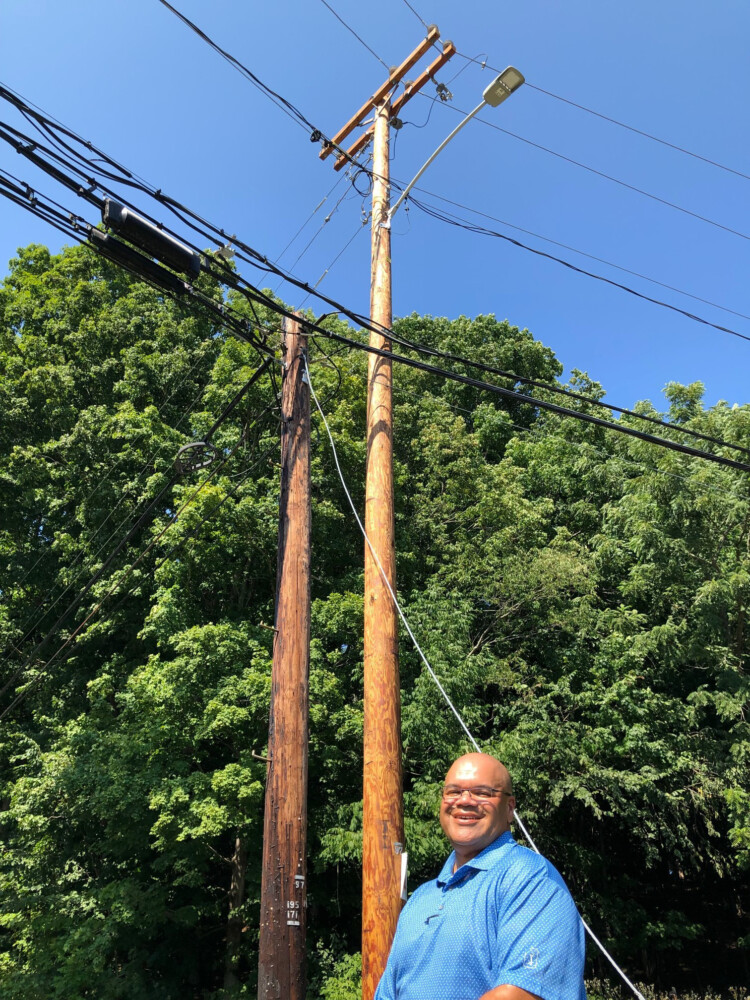

Lloyd Hendrix, who’s overseeing Central Maine Power’s plan to harden its electric grid against storm and tree damage, shows the contrast between an older, thinner utility pole and the taller, stronger version that replaced it along Route 101 in Eliot. The circuit here has among the worst records for power outages in CMP’s system, and is targeted for an upgrade this fall as part of a 10-year, network-wide proposal. Tux Turkel/Staff Writer

“Look right here, more splices,” Hendrix said, pointing to a section where four splices were visible. “There’s a lot of splices on this line.”

This fall, CMP plans to beef up 20 miles of this trouble-prone circuit. Roadside trees will get an enhanced trim. One hundred and sixty poles will be replaced with stronger and taller versions. Automatic switches will be installed to segment the circuit, so if a tree falls on one end, it doesn’t black out all of the 2,392 customers hooked up to it.

What’s happening along these lines in Eliot is part of a larger, 10-year initiative in Maine and New York by CMP’s domestic parent company, Avangrid. The effort has two main goals: Reduce the number of customers that experience outages. Restore power faster when outages do occur.

These goals form the foundation of a request at the Maine Public Utilities Commission to charge CMP customers $29 million over the next two years for a plan aimed at improving 12 of the worst-performing circuits in the system. That breaks down to $8.2 million in 2019 and $17.5 million in 2020, plus another $5 million for more-aggressive tree trimming.

The plan has received little public attention, so far. It’s tucked deep inside CMP’s current rate case, and has been overshadowed by a parallel inquiry into the cause of billing errors that followed the launch of a new software system in late 2017, and subsequent complaints about high bills. The new revenue would be a component in the estimated $3 a month extra that home customers would pay on an average bill, if CMP’s 11 percent rate request is granted in total.

But the hardiness of CMP’s distribution system and its ability to bounce back also can rivet public attention – in an instant. It’s not an exaggeration to say the only thing that gets electric customers more incensed than high bills is having no power at all.

The so-called Halloween windstorm in October 2017 left a record 470,000 customers in the dark, some for more than a week. Restoration cost $69 million, amid complaints that CMP was caught off-guard and mismanaged its response. The PUC found that both CMP and Emera Maine acted reasonably, and could recover restoration costs over time through rates.

But the Halloween storm and similar events in New York have put Avangrid on notice. Noting the impact of a changing climate, the company has observed that “the number of storms of all types and severity that CMP has experienced over the past decade” are growing.” That’s a bad trend in a digital, increasingly electrified society that’s demanding always-on power.

“As businesses and residences rely more on electric vehicles and other electric end uses,” Avangrid wrote in a recent filing at the PUC, “CMP expects that the tolerance for extended outages will continue to diminish.”

CMP’s 2019-2020 Resiliency Plan is the first phase of its program to upgrade 101 circuits responsible for roughly half the number of outages, as well as cumulative hours offline. CMP has a total of 475 distribution circuits.

This section in Eliot is ranked 17th worst of the 101 subpar circuits. It experienced 154 separate events between 2015 and 2017, largely linked to squirrels or other animals, or trees, touching the wires. That led to power being off for 15 hours, on average, over the time period.

A few communities to the north, a section of South Sanford is ranked ninth worst out of 101. From 2015-2017, customers lost power for an average of nearly eight hours a year because of 200 separate events.

CMP’s worst-performing circuit is in Monson, near Greenville. Customers in that rural, heavily wooded area were powerless 30 hours a year from 2015-2017.

All these figures, however, exclude the infamous Halloween storm in 2017.

COMPROMISES ON TREE TRIMMING

But proposed solutions for these vulnerable circuits and the associated cost to ratepayers will be controversial.

For instance: Most outages in Maine are caused by trees contacting power lines. That’s not surprising, as 89 percent of the state is forested and CMP’s service area, with 22,000 miles of overhead wires, is considered among the most wooded in the country. It’s one reason the state topped a national list last year for the average number and duration of outages.

CMP has an approved vegetation management plan in which contractors trim around electric lines every five years to maintain specific clearances, but still allow for an overhead canopy. That’s a desirable compromise for property owners and tree-loving residents, in general. The problem is, 94 percent of tree-related outages are caused by trees outside the approved trim zone.

In its resiliency plan, CMP is proposing what’s called ground-to-sky clearing. That would create an 8-foot space around a tree from the roots to the crown. The company also wants to remove more hazardous trees, such as diseased trees outside CMP’s right-of-way that threaten to fall and cause serious damage. These measures are bound to make some residents unhappy.

Enhanced vegetation management, as CMP calls it, is one of three main strategies for the plan.

A second strategy is infrastructure hardening, which means stronger utility poles and cross arms. Poles that fail to meet inspection standards or are older than 75 years are targeted for replacement.

Selected areas also will have uninsulated wire replaced with a coated product called tree wire. It can come in contact with tree branches, without causing the circuit to trip.

Avangrid has studied the idea of replacing some overhead primary wires with underground cables. But it’s a costly remedy, and no under grounding, as it’s called, is planned for the first two years.

The third strategy is to improve the system’s topology, which is the way circuits are connected.

CMP has a predominantly radial structure, in which miles of lines carry power from substations to homes and businesses. But if a tree falls on one stretch, customers all along the line also lose power.

CMP plans to selectively segment these long lines in part by adding equipment that limits the number of customers hit by a particular outage and making it easier to reroute power.

PRE-WORLD WAR II INFRASTRUCTURE

Along Route 101 in Eliot, Hendrix stopped at locations where these strategies will be put in place.

“Look how thin this pole is,” he remarked, trying to decipher clues about its age from the faded, wood-burned letters and numbers on its surface, the pole’s “birthmark.”

Many of the poles and wires on this circuit were installed around 1935. Hendrix observed the blue-green patina of wire spans near Frost Hill Road. That’s uninsulated copper line, he said, likely strung before the valuable metal was hoarded during World War II. Some of it has multiple splices, and he suspects a row of maples, since trimmed back in a neighbor’s yard, may have been the culprit over the years. More of this area, where the trees received their last haircut in 2016, will be upgraded to tree wire. Some of it already has been.

Farther north, Hendrix pulls over to note a control device installed high above a pole’s crossbars. This is an air break switch, which helps isolate sections of the circuit from broader outages. But this is old, manual technology, which requires a lineman in a bucket truck to reset it. CMP plans to add 11 new switches that will further isolate sections. More important, these smart switches can automatically restore power after temporary faults, or let dispatchers remotely monitor and restore power.

CONTROVERSIAL COSTS

The cost of the doing these things, and to what degree customers or shareholders should foot the bill, is being debated. The PUC’s staff already is contesting key cost estimates, some of which are redacted in the public filing.

CMP has responded with details from an independent study that calculated the benefits and costs of the two-year plan. Many of the figures are redacted, but the study found overall that spending roughly $30 million to upgrade the worst circuits would translate into $84.6 million in benefits. They come largely through aggressive tree trimming and by avoiding the economic impact of power interruptions on homes and businesses.

In a broader sense, though, CMP’s proposal may be stigmatized by the political and public uproar over its billing and customer service investigation.

“The bottom line,” said Barry Hobbins, the state’s public advocate, “is that we’re in a process and until there’s a resolution, asking customers to open their wallets is very difficult.”

Hobbins agreed that it’s crucial to have a resilient electric distribution system, especially in a future in which Maine is expected to rely more on electricity for transportation and heating. But CMP’s mismanagement of the billing system rollout, he said, increases skepticism that the company is making prudent investments in resiliency.

“Instead of looking at long-term planning,” Hobbins said, “we’re spending all our time in a negative way. There’s such a lack of trust.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.