Silas Woodman, a receiver and defensive back for Kennebunk High, is one of the players on the team wearing a helmet equipped with sensors to detect hits to the head. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Silas Woodman, a senior at Kennebunk High, wasn’t keen on the idea of wearing a high-tech football helmet that can detect blows to the head.

“I didn’t want (the sensor) going off all the time, whenever I took a hit,” said Woodman, a wide receiver and defensive back for the Rams.

But it didn’t take long for him to appreciate the new helmet.

“I actually had a concussion a couple of weeks ago (in a game against Bonny Eagle) and the sensor went off. So I know that it works.”

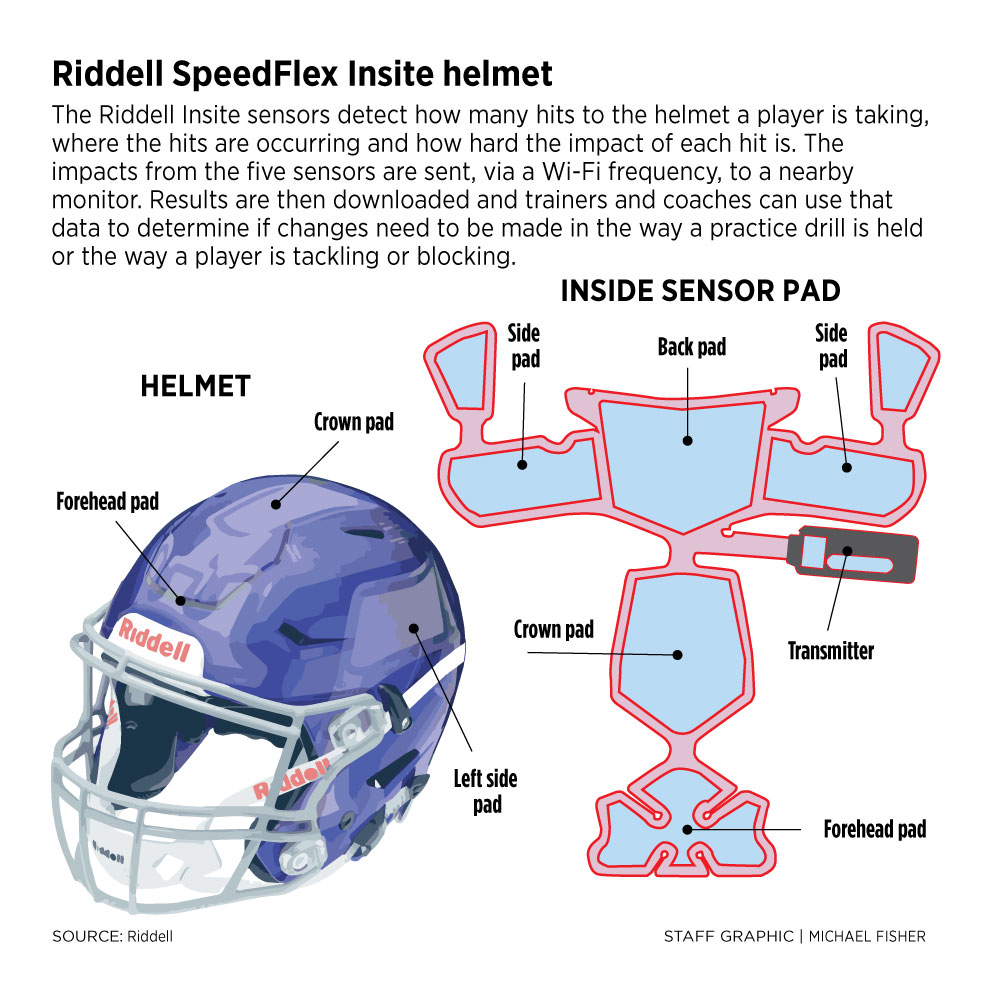

For the first time this fall, high-tech football helmets are being worn by Maine high school players. Kennebunk and Thornton Academy have started to use Riddell’s SpeedFlex Insite helmets, which include five sensors designed to detect how many times a player is hit in the head, where the hits occur and the intensity of the blows.

The helmets have a transmitter that sends data to a hand-held monitor, which registers each hit a player takes to the head – via sounds, lights, images and vibration – as well as how hard the hits are. The information allows athletic trainers or coaches to quickly decide whether a player should be removed from a practice or game to undergo established concussion protocol.

Just as important, the data collected provides an analysis of each day’s practice, showing which drills produce the most hits or which players may need to be instructed on using safer techniques.

“I can look and see if there’s this one kid who’s always hitting the top of his head,” said Arlene Verre, a certified athletic trainer at Kennebunk High for the last 25 years. “We can then teach him to tackle properly. We take that feedback and we use it. It’s another tool that allows coaches to see what’s going on.”

Arlene Verre, a certified athletic trainer at Kennebunk High, holds a monitor that receives signals from sensors inside players’ football helmets Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Concern over the effects of head injuries among football players of all ages has been in the spotlight for years. At the high school level, football has the highest concussion rate of any sport played by boys, according to data gathered in the National High School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study.

Nationally, participation in 11-man high school football has declined for five consecutive years. Last year, it was at its lowest level since 1999. In Maine, the number of boys playing high school football declined by 8 percent over the past five years.

NOT A DIAGNOSTIC MONITOR

Riddell cautions that its SpeedFlex Insite technology won’t prevent concussions or even diagnose them. The helmets are promoted as training tools.

“It’s not a medical or diagnostic monitor. It’s not telling you someone has an injury. It’s saying he took an atypical impact,” said Matt Shimshock, a sales manager for Riddell. “We tell our customers, ‘What do you do when you see an impact?’ You watch the player, you watch him walk to the sideline and you ask him questions. But that’s only for the impacts that you can see. What if there’s a play where a player takes a big hit on the backside? The monitor alerts you to that.”

The SpeedFlex Insite football helmets are used by about 200 colleges, 700 high schools and 100 youth programs across the nation, Shimshock said.

Kennebunk and Thornton Academy are the only two high schools in Maine to use the SpeedFlex Insite helmets, according to Riddell. The schools were invited by Riddell to a seminar in Massachusetts earlier this year to showcase the helmet and its capabilities. Bates College is also using the helmets for the first time this year.

Thornton Academy football players huddle while running drills during a practice last week. The school has 15 SpeedFlex Insite helmets, including those used by quarterback Kobe Gaudette (17) and guard Jack Rogers (55). Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Kennebunk has nine SpeedFlex Insite helmets (among the 39 players on its roster) while Thornton has 15 (among 54 players). Cost is a prohibiting factor. The helmets sell for $500 to $550 – about $100 more than the SpeedFlex helmets without the Insite technology. The inserts, or sensors, can be installed into reconditioned SpeedFlex helmets for $150.

Kennebunk opted to recondition its helmets with the Insite system with funds from its athletic budget. Thornton Academy was aided with a $2,000 grant from the Maine chapter of the National Football Foundation, which provides funding to schools for equipment purchases.

Howie Vandersea, the founder and president of the Maine chapter, said the purchase of the helmets is exactly what the organization is looking for when it provides grants. “If it’s going to help young kids and make (football) safer,” he said, “that’s what we’re going to do.”

Both schools distributed the helmets to players who most likely would be involved in hitting on every play, such as linebackers, linemen and running backs. They are also issued to some quarterbacks, wide receivers and defensive backs.

A helmet without the impact sensors, left, and one with the sensors, right, that are worn by nine Kennebunk High School football players. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Shimshock said the technology has been around since 2003, when it was used primarily for research purposes at the college level. Over 10 years, Riddell collected data on over 3 million impacts. And that allowed the helmet maker to improve the system dramatically, he said.

The SpeedFlex Insite system was first offered to high schools in 2014 but it wasn’t entirely well received. “Some of the feedback we got was that they weren’t getting enough information,” he said. “The sensors were only registering three, four hits a year, which is a good thing. But the coaches wanted more information.”

The NFL stopped using helmets with sensors in 2015 so, according to a New York Times story, it could “continue to review and analyze the research.”

In 2018, Riddell released an upgrade of its Insite sensors. Helmets with the Insite sensors and transmitter weigh a few ounces more than SpeedFlex helmets without, Shimshock said.

William Heinz, chairman of the Maine Principals’ Association’s Sports Medicine Committee and a staff member of the Maine Concussion Management Initiative at Colby College, has concerns over the reliability and accuracy of the sensors and cautions how the collected data are used.

“To use them over the course of the season to see how many hits a player has or how hard he’s been hit doesn’t give you valuable information because we don’t know how hard a player has to get hit to get a concussion,” he said. “(Research) is all over the map how bad a hit has to be before it causes it any damage. … You still have to be vigilant and watch for signs of concussion.”

But, he added, “It is one more tool we have and that’s fabulous.”

SOME RELUCTANCE AT FIRST

The schools that are using it agree. “It’s helping us look at what we’re doing, how can we coach our players better,” said Nick Cooke, the assistant athletic director for athletic performance at Bates College. “It helps us to be better prepared to playing the game at a high level.”

Sixty-two of the 68 Bates players are equipped with the SpeedFlex Insite helmets.

Cooke said the data will be more valuable in the future, when the Bobcats have more numbers to compare. “It takes a little training and effort to figure out what you’re seeing,” he said. “Our commitment is long-term.”

Players at Thornton Academy weren’t exactly thrilled to learn they were getting the high-tech helmets, according to assistant football coach Kirk Agreste and athletic trainer Tony Giordano.

Thornton Academy athletic trainer Tony Giordano holds the remote device that receives a signal from sensors inside high-tech football helmets. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

“I thought I was going to be taken off the field every other play to get checked for a helmet hit,” said senior Cole Paulin, a fullback and linebacker for the Trojans.

Once they understood that wasn’t going to happen, they learned to like the helmets. Paulin would like every player on the field to have one. “Why not?” he said.

Agreste and Giordano monitor the players during practice and then download the Insite data each night for reports on each player wearing the helmets.

“The good thing is that there are 22 guys out there at a time (on the field),” said Giordano. “And you don’t always see what happens in the trenches, so if one of my kids takes a good shot, the sensor will light up and I can check on him.”

Often the data will reveal something interesting. Agreste said that the results showed a lot of helmet hits during practice involving special teams. “And we had a discussion about what we were doing that might be causing that,” he said.

Thornton head coach Kevin Kezal said the data is the best proof a coach can show a player that he is not using proper technique when tackling or blocking. “If all of a sudden we see a kid is taking high-impact hits on the same place, that tells you the kid is dropping his head,” he said. “We have the data to show it. And we can tell him, if you continue to do it, you’re going to get hurt. I think the thing we’re happiest with is that, even in the games, we haven’t seen a lot of high-impact hits.”

Joe Rafferty, in his 41st year as head coach at Kennebunk, said he can now look at the data and see exactly when hits were occurring in practice.

“Say, hypothetically, we see a lot of spikes (in hits) at Wednesday at 3:40 in the afternoon,” he said. “We can look at our practice plan and see what we were doing that might have caused it and how we can change it.

“It is having an impact. It’s comforting for me, as a coach, to have that information.”

Thornton Academy head coach Kevin Kezal directs players during a practice last week. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Neither school employs contact drills in practice as much as in years past. Kezal said the Trojans have had one full-contact practice this season. Most days are in shorts with helmets and shoulder pads, with the focus on fundamentals.

Verre, the Kennebunk trainer, said she has only had one high-impact hit register on the monitor – and that was Woodman’s concussion. “We’re well below the national level,” she said. “And that’s something we can be proud of.”

The players have come to appreciate the helmets. “I feel safer wearing it,” said Kennebunk junior lineman Cam Bennett. “I know if I get a hit, they’re going to recognize it and take me out of the game, even if I don’t want to.”

Thornton Academy quarterback Kobe Gaudette said players aren’t inclined to take themselves out of a practice or game. “As a player, we take hits and just shake it off. But if you’re looking at (the Insite technology) from a health aspect, from a parent’s perspective, it’s great because it protects the players, lets everyone see where the hits are coming.”

Thornton lineman Jack Rogers said his father was glad that he got one of the helmets. “He thought it was extra protection. He thinks we’re lucky to have this technology.”

Kennebunk’s Woodman, who suffered a concussion when he was making a tackle, said he now takes comfort in wearing the helmet.

“It does make me feel a little more safe,” he said. “Sometimes you take a hit and you don’t feel quite right, but you don’t feel (like you should leave the game). I feel that was kind of what my concussion was like. I know a lot of people would play with that and, maybe before, they would have played with it. But with the sensor, it lets you know something happened.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.