Teachers at Coastal Ridge Elementary School in York were still adjusting to mask wearing, physical distancing and new safety precautions when they got the news earlier this month of the first positive coronavirus case at the school.

Two days of remote learning turned into two weeks after an additional two cases were reported and the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention declared an outbreak at the school. Thanks to prior planning, teachers in September had sent students home with “just in case” packets of paper assignments, but they had to shift quickly to communicating with parents via email and recording videos for their students.

“These are kids who didn’t opt to be remote and now they’re remote. Their parents also didn’t ask to be remote, so it was a huge learning curve, and for teachers, too,” said Deb Bradburn, a fourth-grade teacher at Coastal Ridge.

Despite the virus upending their academic plans and complicating every aspect of the school day, Bradburn and other teachers around Maine are keeping a positive attitude. They’re exhausted. They’re stressed. They know they won’t cover as much material as they would in a typical year, but they’re doing their best to keep things as normal as possible for students.

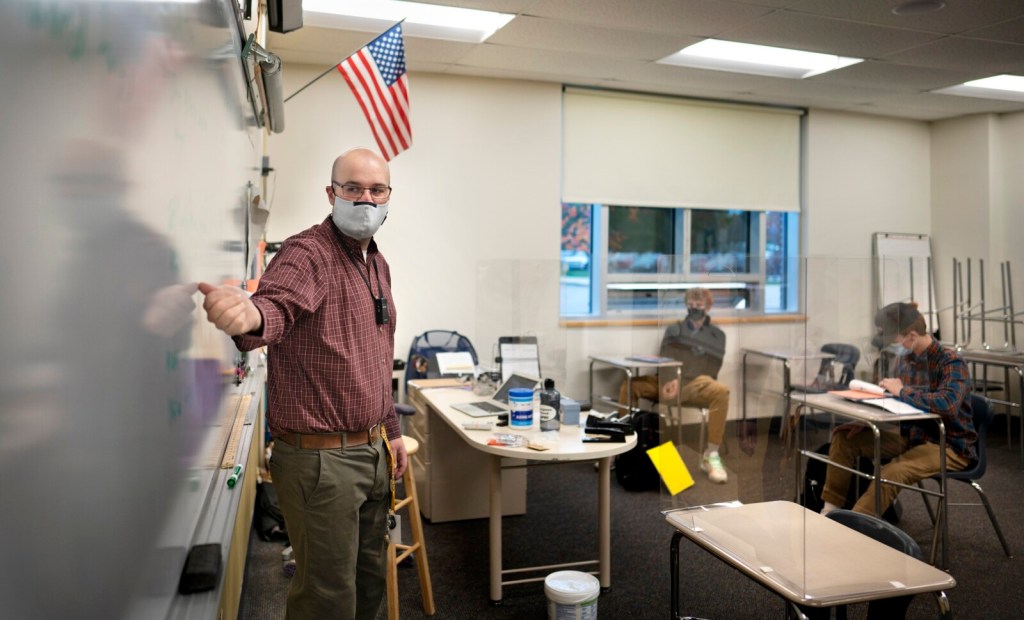

In a classroom transformed by plexiglass, social studies teacher Tom Walsh reviews an assignment with his students at Falmouth High School on Friday. Among the many challenges, Walsh says, “You’re able to accomplish less in the same set of weeks than you used to.” Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer Buy this Photo

Maine is better positioned than many states to reopen schools this year, and most school districts have opted to bring students back for some in-person learning under hybrid models that also involve some remote learning. A total of 113 cases of coronavirus have been reported among students and staff in 66 Maine schools in the last 30 days. Most of the cases have been isolated as opposed to outbreaks, which consist of three or more cases at one location.

Several teachers’ unions expressed health concerns associated with trying to bring students back in-person prior to the start of the school year. And while some of those concerns do still exist, several teachers said their fears have diminished after the first month back at school.

Still, teaching during a pandemic isn’t easy. It requires creativity and diligence as teachers try to enforce social distancing and mask wearing with students. Many teachers have had to come to terms with the fact this isn’t a normal school year and their students probably won’t be learning as much. And then there’s the social and emotional toll that students and teachers alike are experiencing.

At Falmouth High School, social studies teacher Tom Walsh said one of the biggest challenges of teaching during the pandemic comes from seeing his students in-person less and as a result having to adjust the pacing of what he’s teaching. “You’re able to accomplish less in the same set of weeks than you used to,” Walsh said.

Normally Walsh would walk around his classroom, offering feedback and answering questions as they arise each day. Now Walsh is in-person four days per week but he only sees each class he teaches in-person once per week. He said he’s focused on teaching skills, like essay writing, over content, like the dates of a historical event.

Nicole Casasa-Blouin hands out papers to her fourth-graders while teaching outside at Talbot Community School in Portland on Thursday. Casasa-Blouin says the pace of teaching has changed under the school district’s hybrid model and it limits what she’s been able to cover. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer Buy this Photo

Walsh also keeps on hand plans for what will happen if his school has to transition to remote-only learning. Logistically, he thinks it would be too difficult for schools to bring all students back for full in-person learning anytime soon, so he’s hoping for some stability in the hybrid model. “The thing that gives me the most stress is bouncing back and forth between the different systems,” Walsh said. “We haven’t had to do that, but I understand why we could have to if cases uptick.”

Rohan Henry, an English language teacher at Portland High School, is also teaching in-person four days per week right now. Most high school students in Portland are taking their core classes remotely, though English language learners are among select groups that have more in-person time.

But Henry said the school feels far emptier with a reduced student population and that teaching is much more challenging. As an English teacher, Henry said his students rely heavily on being able to read lips and watch facial expressions. He could wear a clear face shield, but prefers an N95 face mask for health reasons.

“They can’t see my lips and I’m disappointed about that but I’m going to go with safety first,” Henry said. “I just try my best to teach them anyway and they are getting it, but it’s slower.”

Nicole Casasa-Blouin, a fourth-grade teacher at Gerald E. Talbot Community School in Portland, also said the pace of teaching has changed under the district’s hybrid model and she’s only able to cover so much new material during the week due to limited in-person days. Casasa-Blouin has two cohorts of students who come in-person two days per week each. Her in-person students come for five hours per day and after they go home she checks in on her remote learners.

“I think I’ve gotten into a good routine,” Casasa-Blouin said. “I definitely am stressed. It’s a lot of work and a lot to manage having in-person and remote. I think we’re all doing the best we can. That includes us as teachers as well as families and students. I find comfort knowing I’m not alone in this and not the only one stressed. The whole community is stressed.”

Annabelle Beam, a fourth-grader in Nicole Casasa-Blouin’s class, raises her hand to ask a question during a class outside at Talbot Community School in Portland on Thursday. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer Buy this Photo

Before school started, Casasa-Blouin said she struggled with the decision of whether she wanted to return in-person, but ultimately decided she missed her students and felt she would be a better teacher in-person. “Once I got over the emotional turmoil with that, I think it’s been going really well,” she said. “I’ve been pleasantly surprised.”

Having smaller-than-normal classes – there are only six students in each of Casasa-Blouin’s cohorts – has helped. And after spending the first few weeks getting down hand washing and physical distancing routines, Casasa-Blouin said she feels safe at school, though she knows things could always change.

“It can be stressful to think about the different scenarios,” Casasa-Blouin said. “I’m really trying to focus on what can I control now and how can I be the best teacher I can be given these circumstances.”

While Cumberland County has consistently been designated “green” in the state’s tri-color school reopening advisory system, meaning in-person instruction can take place, schools in other counties have shifted between green and yellow designations. Teachers at Coastal Ridge in York said the state’s decision to move York County to yellow in early September had little impact on them, though the outbreak this month was a major shift. Superintendent Lou Goscinski said the outbreak was traced back to a youth athletics organization outside of the school and outside the town of York.

Keri Harrod, a second-grade teacher, said she was still working on getting her students to adjust to logistics such as sticking to designated physical distancing spots while eating snacks and keeping masks on when the school went remote for two weeks. Not all students had their district-issued technology devices at that point, so Harrod also had to provide technical support for students trying to figure out how to do schoolwork on different computers and phones at home.

“I think this is the most challenging year I’ve been teaching,” said Harrod, who is in her 10th year as a teacher. “It’s physically exhausting, emotionally exhausting and nothing is the same. We’re putting in so many hours just to figure out how to do what we’re doing.”

York teacher Keri Harrod reads Lois Lowry’s “Gooney Bird Greene” to her second-graders during an outdoor session at Coastal Ridge Elementary School on Friday. “It’s physically exhausting, emotionally exhausting and nothing is the same,” says Harrod. “We’re putting in so many hours just to figure out how to do what we’re doing.” Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer Buy this Photo

Harrod, Bradburn and a third teacher, Jessie Rafferty, who is teaching only remotely this year, said, however, they are happy with how their district and school leadership have responded to the outbreak and throughout the pandemic. Their principal, Sean Murphy, has helped brainstorm ways to make lunch work and create outside learning spaces and been sure to check in on teachers emotionally, the teachers said.

“He keeps us in a positive mindset, so no matter what is thrown at us, we’re going to be OK and our kids are going to be taken care of and our parents will be communicated with,” Bradburn said. “That’s what makes it OK in a very challenging time, is the leadership we’ve had.”

As a teacher, Bradburn tries to do the same to respond to the emotional needs of her students and their families. One of her students this year lost her grandfather to COVID over the summer. At school, Bradburn said she notices the student is very conscientious about physical distancing and is always calculating the amount of space between students.

She said she has been in touch with her mother to talk about how best to support the student. “You need to be sensitive to things like that,” she said. “All the time it’s in the back of your mind.”

In Portland, Henry, the Portland High teacher, also knows the toll that going to school in a pandemic can have on parents. His son is a student at Ocean Avenue Elementary, where Portland Public Schools reported its first case of the virus in mid-October, forcing some students to have to quarantine.

Henry’s wife, who is also a teacher, is teaching remotely this year, so she was able to watch their son while he was home. But Henry knows not all families are so lucky, including many of his high school students’ families.

“The kids I teach, their parents have to be front-line workers,” Henry said. “They’re in retirement homes. They’re in hospitals. They’re CNAs. That’s what they do for a living. It’s a precarious thing and in some ways, I guess I’m on the front line, too. If their parents are and we’re around the same people, in some ways I’m there, too.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.