A prison inmate serving a 75-year sentence for murdering a woman in 1988 has been charged in the separate slaying of Janet Brochu of Winslow a year earlier.

The arrest of Gerald Goodale, 61, in connection with Brochu’s 1987 cold case, came after unspecified new evidence was uncovered and presented to a grand jury, Maine State Police said in a news release on Friday.

Brochu, who was 20 at the time of her death, was out with friends on Dec. 23, 1987, in Waterville when she separated from the group and disappeared, police said at the time. She was last seen leaving a nightclub in Waterville at midnight in the company of a man.

Three months later, in March 1988, her unclothed body was found in the Sebasticook River in Pittsfield.

A Somerset County grand jury on Thursday indicted Goodale, who is currently an inmate at the Maine State Prison in Warren serving a 75-year sentence for the 1988 murder of Geraldine Finn. Maine State Police Detectives met with Goodale on Friday to inform him of the charges in the Brochu case.

“This case represents years of combined work by state, local and county investigators, prosecutors and skilled scientists who never relented in their pursuit of the truth and for justice for this victim, her family, and friends,” Maine State Police Col. John Cote said in a statement.

ANGUISHED PARENTS

Brochu lived with her parents, Geraldine and Albert Brochu, on Cushman Road in Winslow when she disappeared from T. Woody’s, a popular nightclub on The Concourse in Waterville. She had left the bar around midnight with two men on the night of Dec. 23, 1987, police told the Morning Sentinel at the time.

“She left the house at 6 o’clock saying she was going to cash her check and go to McDonald’s,” Geraldine Brochu, Janet Brochu’s adoptive mother, told a reporter at the time.

Geraldine Brochu died at Mount St. Joseph nursing home in Waterville in 2015 at 87; Albert Brochu died at his Winslow home in January this year. He was 91. Janet Brochu was an only child.

Geraldine Brochu said her daughter, who was was 5 feet, 6 inches tall and severely diabetic at the time of her disappearance, required insulin injections twice a day. She worked as a dietary assistant at the then-Seton Unit, Mid-Maine Medical Center, for 1 1/2 years, her mother said at the time.

Janet Brochu reportedly drank alcohol at T. Woody’s that night but was told to leave after bar attendants asked her for identification and discovered she was underage, her mother said police told her at the time. She left with two men and a short time later, one of the men returned to the bar, picked up Janet Brochu’s pocketbook “and said he’d take care of her,” Geraldine Brochu told a reporter.

Her disappearance prompted a coast-to-coast police alert, Waterville police Sgt. Lee Gilbert, said at the time.

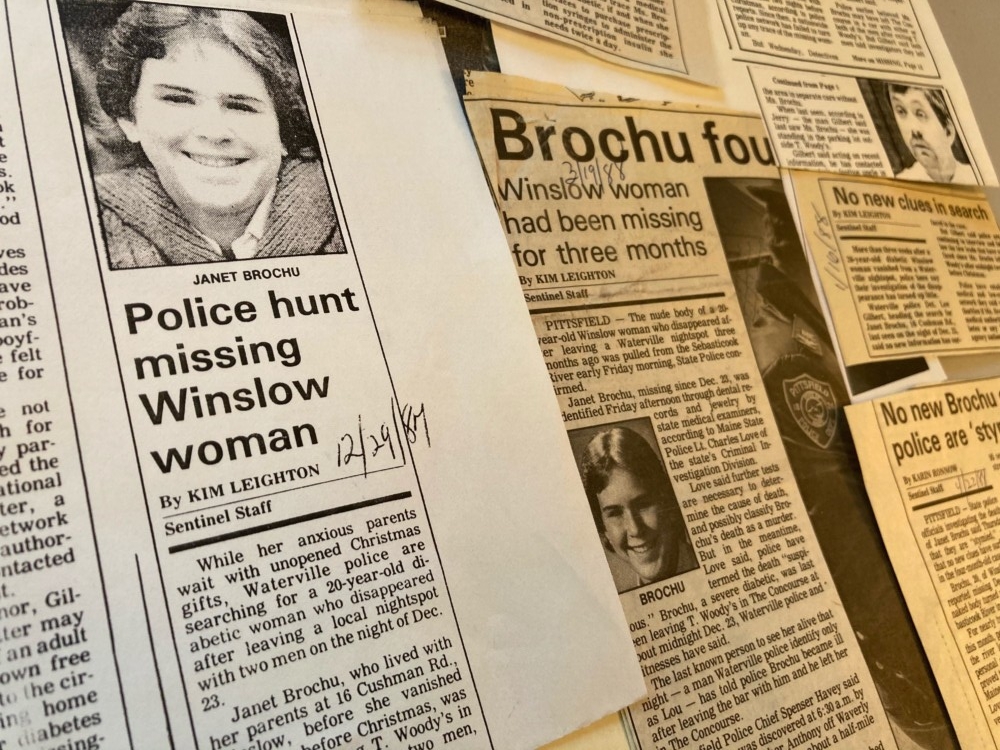

Archived news clippings detail the story of Janet Brochu after she disappeared in 1987 and her body was found three months later.

In January 1988, more than a week after Brochu’s disappearance, Gilbert and police Detective Everett Flannery found one of the two men — who reportedly left T. Woody’s with Brochu — at a bowling center on West River Road. Brochu reportedly had visited the bowling center with a group of friends before going to T. Woody’s and that is where she met the two men Dec. 23.

“The pair have been identified by police only as Jerry and Lou,” a Sentinel story dated Jan. 1, 1988, says. Gilbert said at the time that the men were cooperative and told police they left T. Woody’s in separate cars that night, without Brochu.

The man named “Jerry,” (later determined to be Gerald Goodale), of Waterville, allegedly was the last person to see Brochu alive and told Gilbert she was standing in the parking lot outside T. Woody’s when he left.

By January 1988, the search had widened to include Maine State Police and the Maine Attorney General’s Office.

Divers search the Sebasticook River in April 1988 for personal effects of Janet Brochu, but do not find anything. Morning Sentinel file

On March 19, three months after she disappeared, Janet Brochu’s nude body was pulled from the Sebasticook River in Pittsfield and identified through dental records and jewelry, state police said at the time.

Her body was discovered early in the morning about a half-mile from town off Waverly Avenue by river dam owner Christopher Anthony, according to then-Pittsfield police Chief Spencer Havey, who died in 2016.

The partially frozen body, covered in algae, had washed up against a metal grate that protected the hydropower generators, Havey told a reporter.

In April 1988, divers scoured the Sebasticook River looking for Brochu’s personal effects but did not find anything.

GERALDINE FINN CASE

Five months after Janet Brochu’s body was found, another woman disappeared from a Waterville nightclub and later was found dead.

Geraldine Finn, 23, of Skowhegan, was last seen Aug. 9, 1988, leaving the Pete & Larry’s Lounge at the then-Holiday Inn on upper Main Street in Waterville. Her body was found five days later in a shallow grave, in a wooded area off U.S. Route 201 in Skowhegan.

Finn shared a first name, Geraldine, with Janet Brochu’s mother. The name is a longer version of Gerald (Goodale), later determined to be Finn’s killer.

Goodale lived on Water Street in Waterville’s South End with his parents at the time. Neighbors described him as combative and someone who spent most of his time tinkering with cars behind his parent’s home. State police said he supported himself with odd jobs.

Friends told police after Finn’s disappearance that she was last seen leaving Pete & Larry’s in a blue Chevrolet Blazer driven by Goodale, then 29. Goodale was charged in Finn’s murder Aug. 15, 1998, according to a criminal records check.

According to police reports, Finn had left her pocketbook at Pete & Larry’s when she left around 11 p.m.

Like Brochu, Finn worked in health care, at a Skowhegan nursing home, Woodlawn, according to her parents, Sarah and William Finn. The Finns had lost an infant girl in 1963, as well as a 15-year-old son, Joseph, in 1983, after he was stuck by a hit-and-run driver in Saugus, Massachusetts, where they had lived prior to coming to Maine.

Goodale, who authorities said had strangled Finn, stood trial over five days in Kennebec County Superior Court in Augusta and was found guilty of a Class A charge of murder. He was sentenced on June 9, 1989, to serve 75 years in prison.

Gerald Goodale is led in handcuffs by police after being arrested in June 1989 in connection with the murder of Geraldine Finn. Morning Sentinel file

Goodale said before the court, “I am truly sorry. It wasn’t no murder. It was an accident,” according to a Morning Sentinel story at the time.

Superior Court Justice Donald G. Alexander called Goodale, then 30 years old, a remorseless, predatory and dangerous person and said the sentence was the “minimum necessary with good time to protect society from this man for the rest of his productive life.”

The same day the sentencing story about Goodale ran in the Morning Sentinel, another story ran with it, headlined: “Questions over Brochu death resurface.”

The story said testimony at Goodale’s sentencing “suggests that the books may not be closed on the case of a Winslow woman (Brochu) whose nude body was pulled from the Sebasticook River in Pittsfield last year.”

Goodale was brought in for questioning at least twice after Brochu’s body was found and his truck was searched, according to the story.

“Neither he, nor anyone else, has ever been charged in connection with the death,” the story says.

Medical experts at the time said the condition of Brochu’s body prevented determining a cause of death, which was “fundamental to assembling a homicide prosecution.”

Fern LaRochelle, Maine’s deputy attorney general at the time, argued for a life sentence for Goodale, convinced that the man had also murdered Brochu.

Goodale, he said at the time, “has committed another very serious felony without remorse or regard for the victim’s family.” LaRochelle confirmed afterward that he was talking about the death of Brochu. He said a pre-sentence investigation assembled for Goodale’s sentencing noted investigators had recently questioned him about Brochu’s death.

“It says that Goodale told them that he didn’t do it, but that he knows who did. But he won’t tell who it was,” LaRochelle said.

While Gilbert, the Waterville police sergeant, referred to the two men who were last seen with Brochu as Jerry and Lou, the spelling of the men’s names in the Sentinel story of June 10 and 11, 1989, are “Gerry and Lew.”

“Gerry turned out to be Gerald Goodale,” it says.

Goodale in 1990 appealed his murder conviction in the Finn case but the Maine Supreme Judicial Court upheld the conviction. At the earlier trial, friends of Finn’s pointed to Goodale, saying he identified himself as “John,” after joining them and Finn at Pete & Larry’s. One of Finn’s friends said that Goodale had first circled the Holiday Inn bar in his truck and then through the window, summoned the women outside. The witness said Goodale was sitting, nude, in his truck.

They declined to go skinny-dipping with him and he eventually went back into the bar, clothed, drank a beer and danced five songs with Finn, a friend of hers from Norridgewock said at the time. He and Finn left the bar holding hands, with Finn saying he was going to give her a ride home to Skowhegan.

She never arrived home.

Five days later, her body was found by the property owner, covered in pine needles and sticks, a purse strap wrapped around her neck.

GOODALE’S PAST

After Goodale’s arrest in the Finn case, his mother, siblings and girlfriend described him as a gentle, caring person who couldn’t have murdered anyone.

His mother, Juanita Goodale, said she raised him and two other sons and a daughter in Winslow until the family moved to Florida.

He had attended Winslow elementary, junior high and high schools, but did not graduate, instead completing only the 10th grade. He did not return to school in the fall of 1976, school officials said in 1988.

Goodale enlisted in the U.S. Army instead and served three years, including an 18-month tour of duty in Germany. He was discharged at 21 and moved to Florida to live with his parents. His parents moved to Maine, but he stayed behind in Florida.

He married there and had two children, a boy who was 4 in 1988, and a girl who was 2 that year. The marriage failed and the couple divorced. He came back to Maine, but his children remained in Florida. According to Morning Sentinel stories, he started dating a woman in Waterville late in 1987.

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.