Nineteenth-century Maine is typically recalled as a rough-and-tumble place with farms, forests, sailing ships, steam engines and clothing mills that collectively offered opportunity — and sometimes disaster — for the hard-living Mainers of the era.

But there was then, as now, a different Maine, a place that in just a couple of decades somehow turned out three women opera singers who took leading roles at the most lavish venues on the planet.

After growing up in the Pine Tree State, Lillian Nordica of Farmington, Anna Louise Cary of Wayne and Emma Eames of Portland and Bath each took center stage at opera houses around the globe, growing rich and famous in the process.

They were known not just by opera fans but also by ordinary people who followed tales of their lush and lively careers in the popular press.

The Bangor Daily News in 1916 called the trio the “prima donnas of worldwide fame, who made for Maine a lasting place in the musical world.”

Nordica, who sang professionally in five different decades, is the best-remembered of the trio.

Her fame was such that Coca-Cola hired her to plug its sugary soda, putting her images on advertising signs and trays. Many other companies forked over cash for her to plug their products, too.

Even so, the celebrity of all three of the Maine stars — and the somewhat lesser-known Minnie Plummer Scalar of Norway — has faded to the point of near oblivion. Opera stars in general lost out long ago to purveyors of more radio-friendly performances.

But there is still something striking about the women who grew up in rural Maine yet, thanks to their talents and ambitions, found themselves as adults wearing the finest Paris gowns, festooned with jewelry from Tiffany & Co., standing in the spotlights in Milan, St. Petersburg and the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City.

Their voices took them a long, long way from home.

THE THING ABOUT OPERA

It’s a lot easier to understand Motown than the Met.

After all, the words are in English, the tunes easy to follow and the whole point of the music is to reach as wide an audience as possible.

Opera is tougher.

Even so, Nordica once told writer Mable Wagnells that opera’s art is “so very legitimate” and immediate.

“The painter or the writer can take advice, can be assisted, and has time to consider his work,” she said, “but we must face the music alone, at the point of the bayonet as it were, for every tone must come at the right moment and on the right pitch.”

“The actress has neither of these requirements to meet,” Nordica said. “It is very trying, also, to sing one night in German and the next time in some other language.”

“Indeed, every performance is a creation. No wonder we are so insistent on the applause. A painter or writer can say to himself, if his work is not at first well received, ‘Just wait till I am dead!’ But our fate and fame are decided on the spot.”

ANNA LOUISE CARY

One of the first American singers to gain worldwide fame, Cary grew up in tiny Wayne, a woman so rooted in New England’s history that she could trace her roots back to Mayflower passenger William Brewster, a leader among the early Pilgrims.

Cary’s family moved to both Yarmouth and Gorham during her youth. The youngest of six children, she graduated from Gorham’s female seminary in 1860 before heading to Boston to study music while living with her brother’s family.

Her first public performances were in a Bedford Street church that went so well fans raised the money to send her to Europe to study with the masters in Milan, Paris and London.

In 1867, she debuted in an opera in Copenhagen, Denmark. Critics liked it so well that she soon got offers to sing in Germany and Sweden. Her voice had a range of three-and-a-half octaves, wowing audiences.

From 1870 to 1882, Cary mostly performed in the United States, becoming the first American to perform in a Wagnerian opera along the way.

She performed in premieres of Verdi’s “Requiem” and “Aida,” Bach’s “Magnificat” and “Christmas Oratorio,” and Boito’s “Mefistofele.”

Reviewing “Aida,” The New York Times wrote, “It is not too much to say that there is no finer performance on the operatic stage than Miss Cary’s Amneris.”

The Chicago Evening Post in 1872 said Cary was “the leading contralto and mezzo-soprano among American children of song.”

The state of Maine’s 1875 fisheries report couldn’t help tossing in an appreciation of Cary, calling her “a land-locked siren” as it noted the many terms for Maine’s wondrous freshwater salmon.

The New York Post wrote about Cary’s ability to emit “the most beautiful, birdlike notes to which the dumbfounded hearers had ever listened.”

Yet at the height of her fame, she married banker Charles Raymond and quit singing professionally.

Critic Robert Grau called her “the beautiful and superb” Cary, and noted that she “retired while her triumphs were unbounded.”

Memories of her ability lingered, though. Two decades after her 1921 death in Connecticut, the Brooklyn Eagle recalled Cary as “one of the great American singers” of her day.

Sadly, it appears there are no recordings of her singing.

Fortunately, the voices of both Nordica and Eames were captured for eternity later in their careers, emerging from the static with a purity that can still stir souls.

LILLIAN NORDICA

Born in a small house on a typically hardscrabble farm in rural Maine in 1857, Lillian Norton came from hearty stock. Her great grandfather was a ship’s captain from Martha’s Vineyard and her grandfather, “Camp Meeting” John Allen, grew famous as one of New England’s great religious revivalists.

But Norton, the youngest of four daughters who survived infancy, had little prospect of making a name for herself as she grew up on the family’s little place in Farmington.

Her older sister Willie, though, had such a sweet voice that her family decided to move to Boston so she could study at the New England Conservatory. Norton’s father became a photographer while her mother got a job at Jordan Marsh.

Music started to seep into Norton’s days right from the start.

In a letter the singer wrote years later, she mentioned that her mother once told her that even before she could speak, she could follow a musical scale.

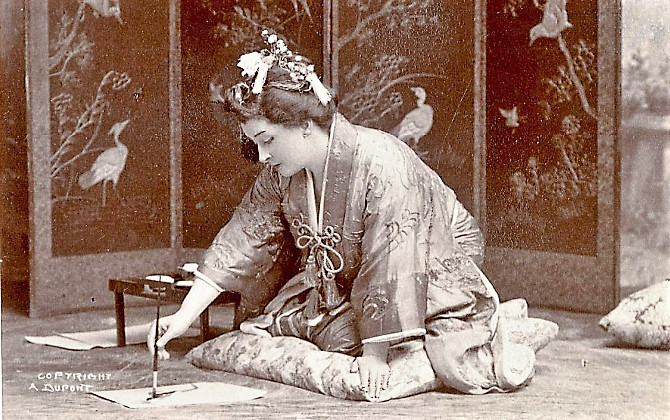

A 1910 Coca-Cola advertisement featuring Lillian Nordica, who appeared in many of the soft drink maker’s early ads. Coca-Cola Co.

As a toddler, she sat at a little square piano in church and sang “Little Drops of Water” so nicely the audience applauded. Norton said she burst into tears instead of playing an encore.

William Armstrong wrote that Norton told him she’d been bribed not to sing along with Willie’s arias as her sister practiced. “My sisters were driven to pay me not to sing,” Norton recalled in her letter.

When Willie died of typhoid at age 17, a common killer in those days, Norton quit public school and took her sister’s place at the conservatory, an experience that sometimes left her “stained with tears and sodden with discouragement,” Armstrong later recorded.

But Norton proved a good student, mastering skills that she soon got a chance to polish with the best teachers in Europe after a successful stint with Patrick Gilmore and his band touring the U.S. and Europe.

By 1878, she was performing “La Traviata” in Italy every night for three months, earning $1 per show, a pittance even then.

“I have had a grand success,” she wrote to her father back in Boston, with nine curtain calls the first night. “Such yelling and shouting you never heard.”

She soon changed her name to Lillian Nordica, which struck everyone involved as more stage friendly, and began getting ever better parts. She sang at the Royal Opera House in London, the Bayreuth Festival in Germany and at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, where she worked off and on for two decades, often in Wagnerian heroine roles.

Nordica married three times, including her first to a distant cousin who vanished in a balloon flight over the English Channel. Her loves, business disputes and wealth were frequently mentioned in news stories around the globe, which also credited her with kindness and warmth.

She called her hometown in Maine “the loveliest spot on earth” and at least twice returned to perform charitable concerts in Farmington, one of them to raise money for kerosene lighting for municipal streets. The last time, in 1911, wearing a white satin dress and more jewelry than Franklin County had ever seen, she ended the concert by singing “Home, Sweet Home.”

Opera star and Farmington native Lillian Nordica pictured on an ocean liner in 1909 by Bain News Service. Library of Congress

Nordica died in 1914 after a ship on which she was traveling got stuck on a reef as it headed to what became Jakarta, Indonesia. She caught pneumonia and later died in Jakarta, the story featured on front pages everywhere.

The Philadelphia Inquirer lamented the loss, calling her “the greatest operatic artist this country has yet produced.”

As long as people lived who remembered her, Nordica remained a vivid figure.

In 1942, with war raging around the globe, Maine Gov. Sumner Sewall accepted a portrait of Nordica by George Kirtland Bishop, the first painting of “a daughter of Maine” to hang in the Hall of Flags at the State House. It had graced the walls of the Metropolitan Opera for a year before it got to shipped to Augusta.

Sewall pointed out that Nordica’s ancestors “were pioneers in Maine wilderness” and that she had “reached by the same unflinching courage, toil and ambition higher achievements in the lyric drama than any other American before or since,” recognized among “the world’s greatest singers.”

The Nordica Memorial Homestead, a museum and historic site, operates out of the house where Nordica was born. It has lots of memorabilia and information about the famed singer and her life.

EMMA EAMES

A wire service report of Nordica’s death in far-off Java mentioned that both she and Eames “were of old New England stock, both claimed by the state of Maine, and they made up a notable contribution to the operatic world.”

Called “the most glorious of American singers” by the American Weekly, Eames followed the same path that Cary and Nordica took from small-town Maine to Boston, where she learned the techniques that gave shape to her talent.

Eames came to her grandparents’ home on Washington Street in Bath as a toddler after her 1865 birth in Shanghai, where her father practiced law.

She recalled to a reporter in Louisville in 1912 that “my Puritan grandmother taught me to hold the reins over a restless temperament.” Eames was told to do her best always – and when she fell short, she said, it “caused me many agonies.”

Friends recalled her to The Boston Globe years later as “one of the jolliest young misses” of the day.

They said Eames was scholarly, always fussing with her nails and fond of pranks. Once in high school, they said, she climbed the outer wall of the building until she could peer in a second-floor window. The principal stood there and told her to return to earth.

Classmates said they never saw any indication that Eames had a special talent for singing, but by high school she was traveling to Portland regularly for lessons.

She later moved to Boston for more training and then Eames headed for Europe as both Nordica and Cary had done before her.

The elderly composer Charles Gounod heard her sing in Paris and immediately cast her in a starring role in his opera “Roméo et Juliette,” which made her instantly famous.

A beautiful high soprano voice brought her role after role in the top shows at the best opera houses across Europe and the United States.

Only a few years after her debut in Paris, the Brooklyn Standard Union reviewed an Eames appearance as the lurid heroine in “Tosca” at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. It said she “looks the beautiful diva” and brings “force and feeling to the role “and sings it as only Emma Eames can.”

She had a reputation as rather a cool figure on stage, focused on her voice and perhaps a tad lackluster in her acting.

But she had her moments.

During a performance of “Lohengrin” at the Met, she got an argument with another woman singer while they stood in the wings before the second act. Eames got so mad that she slapped Kathie Sanger-Bettaque. When reporters quizzed the victim later, she called the incident regrettable “but I was so glad to see some vestige of emotion from Madame Eames.”

Eames kept performing, often at the Met, until she decided in 1912 that she’d done enough, quitting at the height of her career.

“When you strike your high note, retire,” Eames said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.