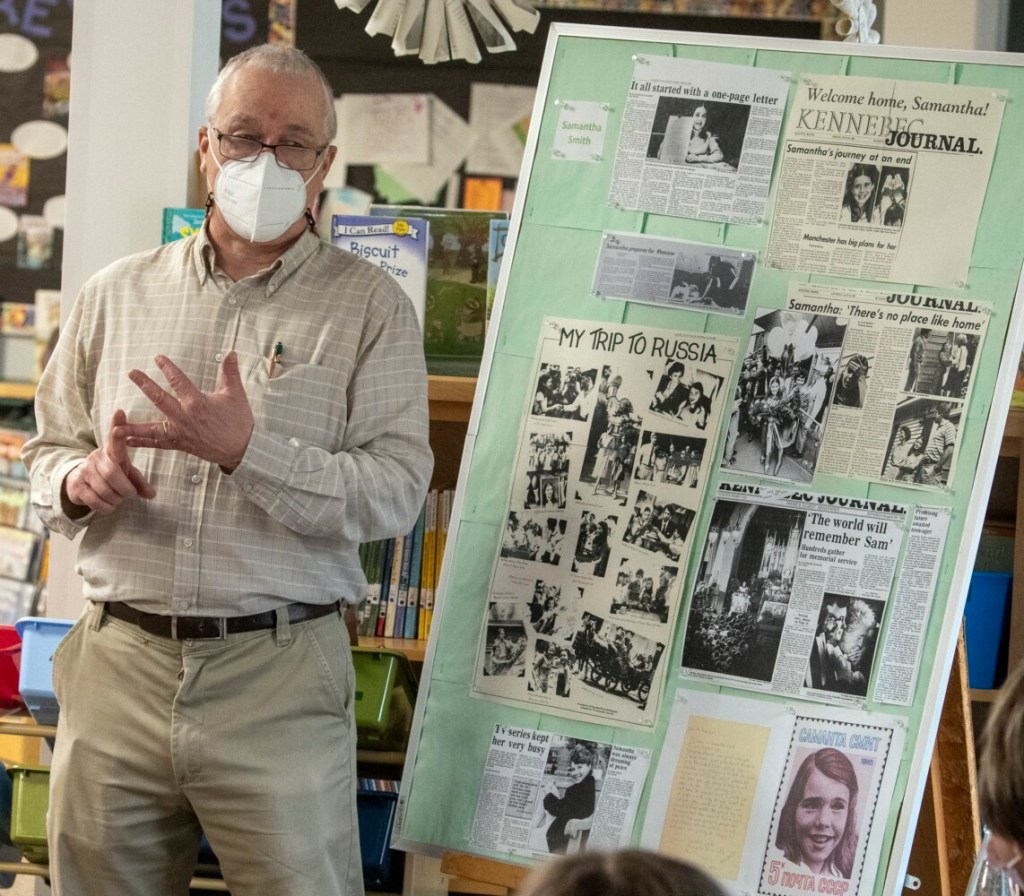

MANCHESTER — “It all started with a one-page letter,” read the headline of a 1985 issue of the Kennebec Journal, displayed on a bulletin board Tuesday in the corner of the Manchester Elementary School library. Alongside it were several other newspaper clippings from when Maine-born Samantha Smith sent a letter to the Soviet Union in 1982, urging for peace.

The piece of mail marked a “world-changing” event for 10-year-old Samantha and her community of Manchester. As the 40th anniversary of the letter approaches this November, Manchester Elementary teachers have realized how relevant her story is to today’s current events.

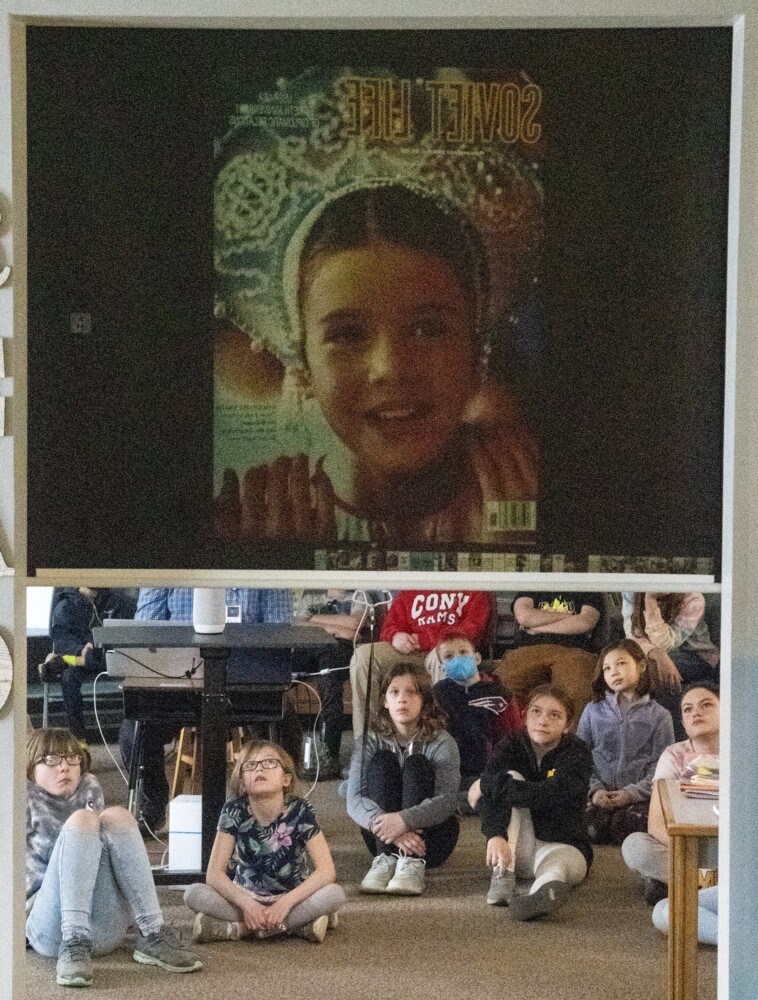

Students view a photo of Samantha Smith during a presentation by Mary O’Brien, left, on Tuesday at the Manchester Elementary School library. Joe Phelan/Kennebec Journal

“Her life became completely different because she asked a question about something in the news, and something that made her scared,” teacher Mary O’Brien said. “I’m not saying to become famous, but to ask questions when you have them.”

Samantha is regularly talked about during the “World Changers” curriculum at the 3rd grade level at Manchester Elementary School, where she attended in the 1980s. But because of the pandemic, the current 4th and 5th graders missed out on her story, so they were given a robust presentation Tuesday morning from teachers who knew her and went to school with her, as well as Joe Owen, a former Kennebec Journal reporter who met Samantha and wrote a story about her before she embarked to the Soviet Union.

Samantha died in a 1985 plane crash, at 13.

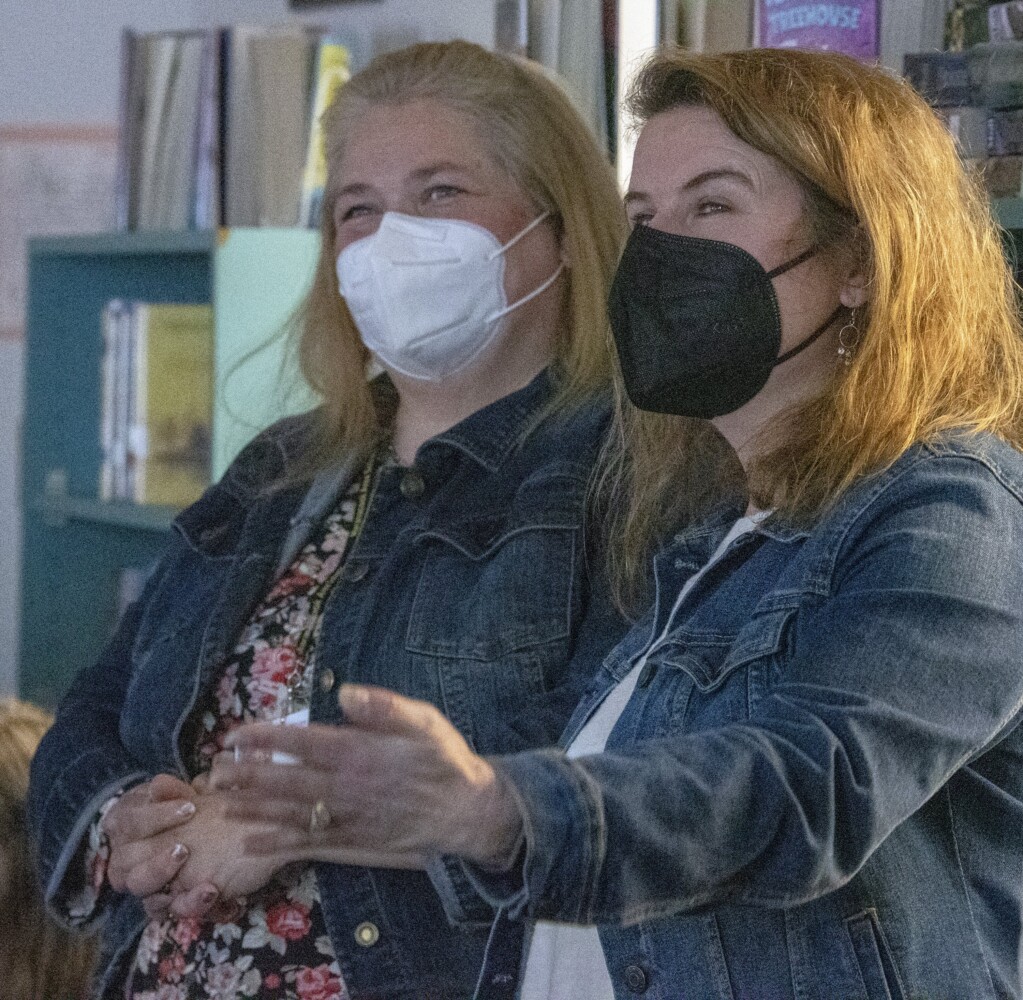

The teachers — O’Brien, Jessica Dwyer and Shannon Cole — took the students through Samantha’s story and shared some of their own personal stories about her. Dwyer was Samantha’s best friend and Cole had Spanish class with her. O’Brien started teaching the year after Samantha died and recalled the sorrow the school felt the school year after her death.

O’Brien reiterated the point to the students that Samantha had seen something she thought was “scary” in the news and asked her parents — Manchester residents Arthur Smith and Jane Goshorn — about it.

Her mother encouraged Samantha to write a letter to Yuri Andropov, then general secretary of the Communist Party and premier of the Soviet Union. A year later, in 1983, she received a reply — but not until a reporter visited the elementary school to interview her and ask if she heard back from the Soviet leader. Samantha’s letter was printed in a newspaper in the Soviet Union.

“If you hear things on the news that make you scared, or worried, ask questions and talk to an adult, like she did,” O’Brien said during the presentation, strongly alluding to the ongoing crisis in Ukraine.

When Samantha received her letter back from the Soviet Union, her world as she knew it, changed overnight.

In the letter, Andropov asked her and her family to take a trip to the Soviet Union and invited her to attend a summer camp there. Before she traveled, she met Owen, who helped Samantha pick out potato pins and other memorabilia to bring as gifts on her trip.

On Tuesday, Owen explained to the Manchester students what the Soviet Union was and showed them a map of the republics that composed it. He told them how Samantha never got to see “peace” within the state, which crumbled six years after her death.

Samantha Smith with a letter she received from Soviet Premier Yuri Andropov in 1983. Cheryl Denz/Kennebec Journal file

Dwyer and Cole talked about establishing “Project SAME,” or the Samantha Smith Soviet-American Exchange, with former Maranacook Community High School teacher William Preble after Samantha’s death. The motto of the club was, “All kids are the S.A.M.E,” and the teachers said it felt especially true when they realized the love for Samantha both the U.S. and Soviet Union had, despite being completely different.

“We wore the motto on everything, on T-shirts, sweatshirts, trying to encourage the idea of peace,” Cole said to the students. “And you have to understand, we were living in fear of the Soviet Union, and to have this relationship, it was a big change.”

Through the program, students from Maine were able to take a trip to the Soviet Union, then the year after, Soviet students could visit Maine. The students from the Soviet Union came to Maine to attend a summer camp in Hope, and on the anniversary of Samantha’s death, they all shared stores, hugged and cried together.

Manchester Elementary workers Shannon Cole, left, and Jessica Dwyer talk about their late school classmate Samantha Smith during a presentation Tuesday in the Manchester Elementary School library. Joe Phelan/Kennebec Journal

No language barrier could misinterpret the love they shared for her.

“We are all the same was our motto, but we are no different, we couldn’t speak the same language, but we were all the same,” Cole said to the students. “When we hear on the news about other countries, we can think they are bad from what we hear, but deep down they are the same as us. My takeaway is: We are all the same when it comes down to heart.”

Dwyer was able to visit the Soviet Union to celebrate Samantha’s life and had to experience it in the same way Samantha had, following in her footsteps. She said Samantha “was so famous” over there.

To this day, Dwyer gets inquiries from other schools across the country asking if she can share more information on Samantha and she even gets emails from what was formerly the Soviet Union, asking for her to share. “She is still very much alive in people’s hearts,” Dwyer said.

O’Brien ended the presentation by urging students to “be the change you want to see,” and encouraged them to ask questions.

“Every decision on how we treat the Earth, our friends, our family — it makes a difference,” she said. “I don’t expect you all to change the world, but in your tiny world, you can make a difference.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.