BRIDGTON — Rufus Porter was a 19th-century artist who painted portraits and wall murals.

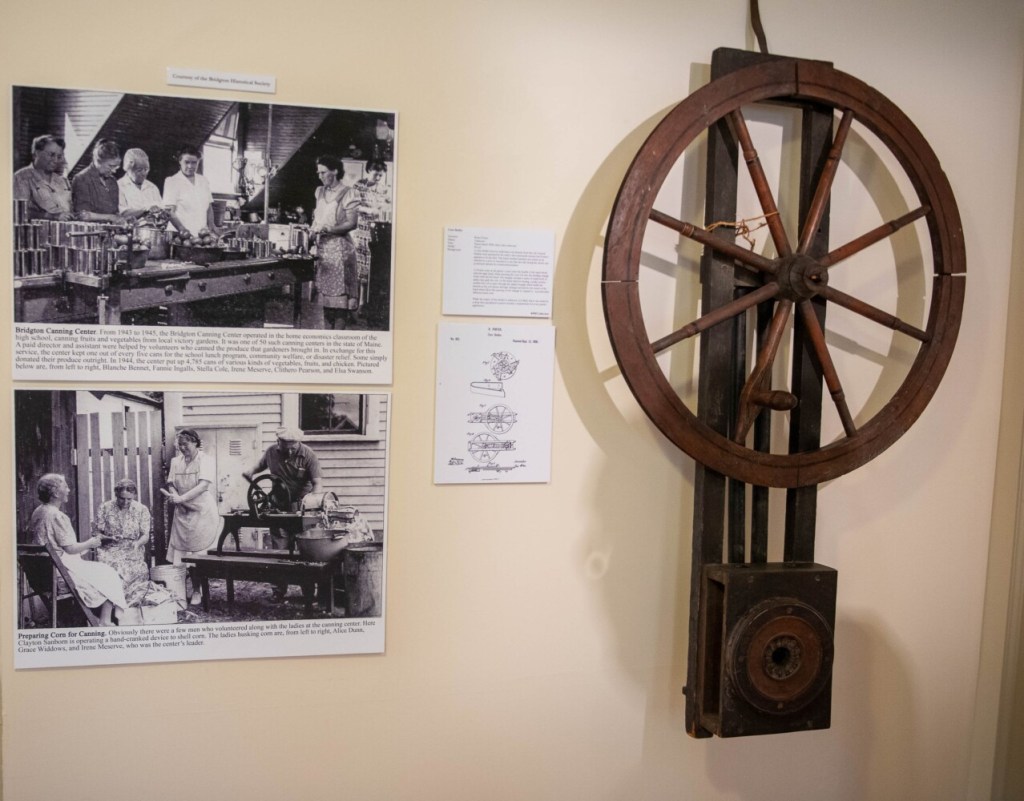

He also invented railway signals, churns, a life preserver, a cheese press and a revolving rifle. A washing machine, a fire alarm, a horse-powered boat. A combination chair/cane with folding parts. A corn sheller. A rotary pump later used in heart and lung transplants. He designed the elevated railway that opened in Chicago in 1888.

He conceived of an “aerial locomotive” to carry gold miners from the New York to California.

He founded Scientific American magazine in 1845.

Rufus Porter is shown in this 1872 photographic print by an unidentified photographer.

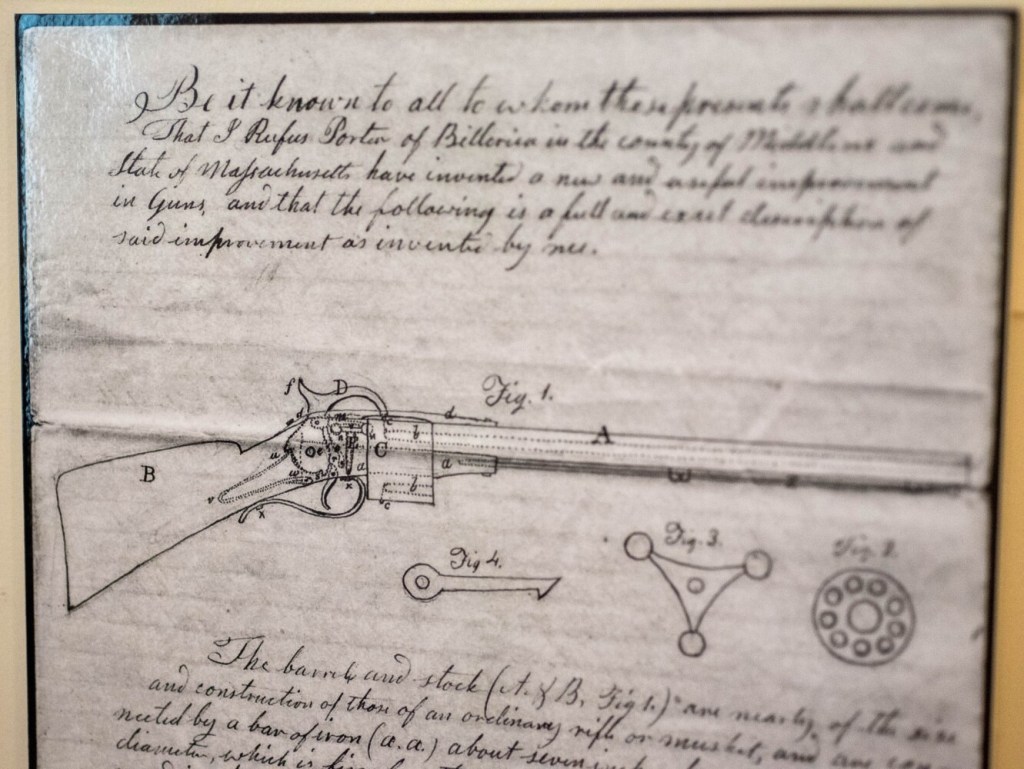

Porter filed 100 or more patents with the U.S. Patent Office that burned down in 1836. To see a list of surviving patents and known inventions, go to c362e1_969e0d4fafe34ce48889d30ade604be5.pdf (rufusportermuseum.org)

“He was a Renaissance man: an artist, inventor, teacher, journalist,” said Lynn Welbourn, a volunteer tour guide at the Rufus Porter Museum of Art and Ingenuity. “He was the original STEM guy.”

The airy museum on Main Street in Bridgton houses displays of sketches with descriptions of how the inventions worked, a portrait room and original copies of Scientific American from the 1800s.

An adjacent museum building, the former home of a local minister named Nathan Church, contains wall-sized murals painted directly onto the plaster by members of the Rufus Porter School of Landscape Artists and Porter’s nephew Jonathan Poor.

Porter was ahead of his time in several ways, according to the museum’s website. He began his artistic life as a decorative painter. He moved on to portraits and later painted the murals that made him famous.

“He painted what he knew — landscapes depicting the farms around Bridgton, Maine, his childhood home, and seaport scenes of Portland, Maine, where he lived and studied as a young man.”

Porter patented inventions that were useful in the home, on the farm, and in the factory. The design for his revolving rifle cylinder helped revolutionize the munitions industry.

His Scientific American magazine encouraged innovation in American arts and sciences. “This pioneering attempt at progressive journalism often included clarion calls to clear the way for a bright and promising future.

“Porter set a tone of excitement for an approaching age where thought and action led the way out of a dark and restrictive past.”

He was born in West Boxford, Mass., on May 1, 1792, a descendant of Puritan settlers. His family moved to Bridgton when he was a child. He received a total of six months of formal schooling at Fryeburg Academy, Welbourn said.

“He was self-taught and curious, a true entrepreneur,” she said. “Inventions were very important to him. But he was a terrible businessman.”

The New England Historical Society described Porter as “a classic Yankee of the early 19th century, part peddler, part itinerant artist, part inventor … he took to the road selling what people would buy at the time.” The society hails Porter as “the Yankee Da Vinci.”

He “liked coming up with new ways to do things. As for getting patents and making money from his ideas, well, not so much,” according to the society’s website.

He sold the rights to his revolving rifle cylinder to Samuel Colt for $100. He also sold his elevated railway concept. He sold Scientific American for $800 just 10 months after he started it in 1845, but he remained as editor for another 18 months. He continued to contribute columns and poetry for the remainder of his life.

He patented only a fraction of his inventions.

He gave away his mural-painting techniques — how he mixed paints and used stencils for greater efficiency — in a book titled “Curious Arts,” which is available in the museum’s gift shop.

His “flying ship” design, imagined in 1820 and conceived in 1849, predated the dirigible by many years, but it never got off the ground, Welbourn said.

“It was his life dream, but it was never built,” she said.

The design called for an 800-foot-long, zeppelin-type structure that could carry up to 100 passengers. He built a 20-foot scale model, displayed at the museum with detailed dimensions.

According to the New England Historical Society website, Porter had “such confidence in his invention that he asked for down payments of $50 for a $200 New York-to-California fare on his aerial locomotive.”

However, a tornado destroyed his first model, rowdy onlookers destroyed his second, and technical troubles tanked the third, according to the society.

ON THE ROAD

Porter also was an itinerant, described in a museum display as an “entrepreneur who employed travel and speculative risk.”

He traveled the East Coast by carriage from Maine to Virginia painting portraits along the way.

“He had a painted cart to draw attention,” Welbourn said.

According to the New England Historical Society, Porter would “come to town with his nephew Jonathan D. Poor and a camera obscura mounted on a cart decorated with flags.”

The camera obscura was a box with a lens and a mirror that projected the sitter’s image onto a piece of paper.

He drummed up business by passing out handbills with announcements, like this one from 1832:

“The Subscriber respectfully informs the Ladies and Gentlemen of Haverhill and its vicinity, that he continues to paint correct Likenesses in full Colours for two Dollars at his room at Mr. Brown’s tavern, where he will remain two or three Days longer. (No Likeness, No Pay.)”

Sometimes he’d paint 20 portraits a day. He also painted silhouettes when they became wildly popular. He could finish one in 15 minutes, and he charged 20 cents for each.

His travels included stopping to paint murals. However, he didn’t sign them, Welbourn said. “We can only say that a mural is done in his style or appears to be his.”

His used his quick method of stenciling to paint at least 160 walls in farmhouses and taverns throughout New England, according to the New England Historical Society.

“It was quite the thing to stencil your walls in 1829,” according to the society. “That year a commentator wrote, ‘You can hardly open the door of a best room anywhere, without surprizing or being surprized by the picture of somebody plastered to the wall and staring at you with both eyes and a bunch of flowers.’”

Porter was involved in decorating the interior of the Hancock Inn in New Hampshire. He also painted murals on the walls of the Kent House in Lyme, N.H., the Birchwood Inn in Temple, N.H., the Damon Tavern in North Reading, Mass., and the Mural House in Greene, Maine, to name a few, according to the society’s website.

Porter’s art “touched the lives of rural New Englanders in a truly special way,” according to earlyamericanpainters.com.

“He covered their walls with peaceful and serene folk art landscapes and colorful vistas of rural life that spoke to patriotism, pride in America, and the bounty of this young and plentiful country.

“The lives of rural New Englanders were forever enhanced by Porter’s scenic landscape murals. Dark interiors and plain plastered walls of their homes were made bright with the hope and promise of spring.”

Porter died in 1884 at the age of 92 at the home of one of his 16 children, son Rufus Frank Porter, in West Haven, Connecticut.

If you have a suggestion for coverage of a favorite Maine museum in central and western Maine, contact writer Karen Kreworuka at kkreworuka@sunjournal.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.