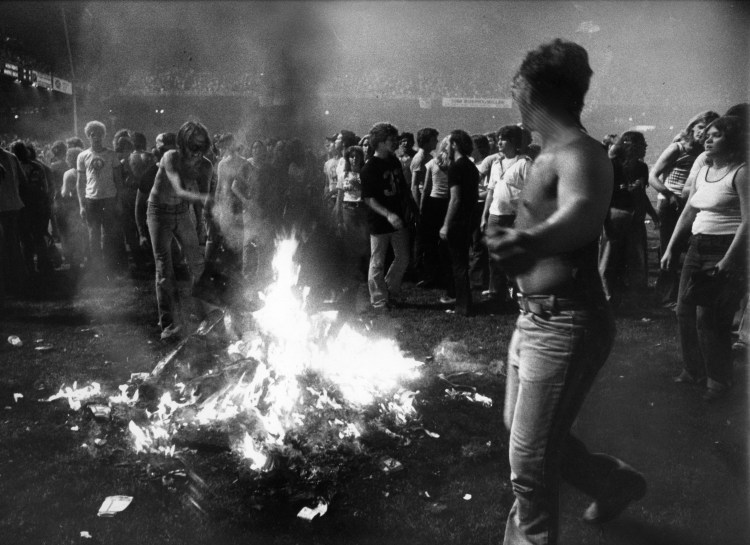

Grainy TV news footage from 1979 shows thousands of people swarming over the field at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, burning stacks of dance records and holding banners that read “Disco Sucks.”

For two Maine filmmakers looking to tell stories with cultural impact, the footage was eye-opening and worth exploring.

“It’s kind of astonishing that it happened. Your first glance at it, you think, that’s a pretty simple explanation, this episode of hate broke out in a ballpark in Chicago,” said Rushmore DeNooyer, of Lone Wolf Media in South Portland. “But as we looked into it, it turned out to have many dimensions and different perspectives.”

DeNooyer and Lone Wolf Media co-owner Lisa Quijano Wolfinger used the “Disco Demolition Night” promotion at a baseball stadium 44 years ago as the focal point for their new film “The War on Disco,” which debuts Monday at 9 p.m. on PBS stations, as part of the documentary series “American Experience.” It will also stream on PBS.org.

Both Wolfinger and DeNooyer were producers on the film, while DeNooyer was the writer and Wolfinger the director.

Lisa Quijano Wolfinger directed the documentary “The War on Disco.” Photo courtesy of Lone Wolf Media

The one-hour film explores the backlash against disco music in the late 1970s – most dramatically illustrated by the Comiskey Park riot – and features scholars and observers drawing parallels to today’s culture wars. It raises questions about whether the rage against disco was fueled by racism and anti-LGBTQ sentiments.

The film lays out the backdrop for disco’s emergence in the early 1970s at urban clubs, places that were often refuges for Black people, members of the LGBTQ community and others who sought safe public spaces. Entertainment executives began to capitalize on the music’s growing popularity and took it mainstream, most notably with the blockbuster film “Saturday Night Fever” in 1977 and the top-selling soundtrack featuring The Bee Gees. The music’s mainstream popularity prompted many radio stations to change their formats to disco, and its rise was symbolized by the opening of celebrity disco venues like Studio 54 in Manhattan. Disco became seen by some as elitist, effeminate and too commercial.

The film’s commentators suggest that many people – especially white, working-class men in economically depressed areas – may have felt threatened by the fashions and themes that were part of the disco scene. Disco came to be seen “as a sign of exclusivity and elitism” to some working class people, said Adam Green, a history professor at the University of Chicago who comments throughout the film.

“There’s a looseness, a flamboyance associated with gay dance clubs in New York and disco embraces that flamboyance,” said Wolfinger. “So you’ve got a musical genre that is associated with a more effeminate male masculinity. I think it opens up a lot of uncomfortable questions for young American males around the country. Am I macho if I dress up in the polyester suit and I’m going to be a really good dancer? Or does that somehow detract from my masculinity? Or there are folks saying, ‘I can’t do that, I can’t dance that way, I don’t have the money to buy a fancy suit, I can’t compete on the dance floor,’ so I’m going to resent it. ”

Based in South Portland, Lone Wolf Media has produced dozens of documentaries in the past 25 years, for Discovery, PBS, ABC and Smithsonian Channel, among other networks. Wolfinger produces and directs the current ABC true crime series “Wild Crime,” which streams on Hulu. She has shot some of the re-enactment scenes for that series in various Maine locations.

“The War on Disco” uses a lot of footage from the time, including at dance clubs and among groups of young people in the late 1970s extolling rock as real music and disco as something to be mocked, shallow and superficial. The footage of the “Disco Demolition Night” and the events leading up to it are especially riveting.

The promotion was sparked by a Chicago rock deejay – described in the film as an early “shock jock” – named Steve Dahl. He had lost his job at a rock station when the format switched to disco, got a new job at another Chicago station, and went on a public campaign to degrade disco as inferior to rock, a music that needed to go away.

Comiskey Park was home to the Chicago White Sox, at that time owned by Bill Veeck, known for unusual promotions aimed at drawing more people to games. When he owned the St. Louis Browns in 1951, he had hired the 3-foot-7 Eddie Gaedel to pinch hit during a game. Another time, he had a promotion that allowed fans to make decisions about the game instead of the manager.

The White Sox had held a “Disco Night” in 1977, so when Veeck’s son and promotion manager, Mike Veeck, heard about Dahl and his anti-disco campaign, he agreed to host the “Disco Demolition Night.” People were asked to bring disco records to the park on July 12, 1979, and watch them get blown up between games of a doubleheader.

The White Sox were hoping the promotion would bring an additional 5,000 fans out during a season when attendance was poor, according to the film. Instead more than 50,000 jammed the park – which officially held about 44,000 – and thousands more were turned away. People chanted “disco sucks” and held banners that said the same thing. After Dahl officiated the explosion that destroyed the giant pile of records, fans stormed the field and would not leave. They set fires and destroyed ballpark equipment. Despite pleas from Veeck and others for the crowd to disperse, it did not, and the second game was canceled.

After “Disco Demolition Night,” many radio stations switched formats or stopped playing disco. The music was changing and evolving and probably would not have remained as popular anyway, Wolfinger said, but the incident drew into sharp focus how polarizing the music and what it stood for had become.

A capacity crowd storms the field at Comiskey Park in Chicago on Disco Demolition Night in 1979. Photo courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Several scholars in the film make the point that the anti-disco sentiment of the 1970s was a continuation of tensions of earlier culture clashes about sex, feminism, gender and race. And those tensions are still with us.

“All of American history is defined by culture wars,” said one of the scholars in the film, Jefferson Cowie, a Vanderbilt University Professor of History and author of “Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class.” “But in the 1970s, an entire new front opened up in the battle over the culture. The Civil Rights movement, the women’s movement, the gay rights movement come along and say, ‘Hey, we want in too.’ And that’s why the 1970s are the foundation of our own time because we’re still battling over these same questions.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.